Backyard Chickens, Then And Now

Posted by Gunnar Rice on Apr 26th 2020

To trace the roots of the current explosion in chicken keeping, you would probably want to consider the influence of Martha Stewart, who trumpeted the appeal of the blue-green eggs produced by her Araucana chickens. The Slow Food locavore movement would be another recent influence. You might even go back to the 1970's and give a nod to Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Catalogue, which promoted interest in the rural lifestyle.

Whatever the cause, the results are impressive. Keeping chickens in a suburban back yard no longer seems eccentric but merely an adjunct to the foodie movement with its concomitant easy availability of such previously little known grocery items as kombucha, coconut oil, and kale. Some people even set up coops in cities, which may be frowned upon by neighbors and the law. But chicken owners have a point: eggs laid by chickens with access to grass and bugs are dramatically different than those of factory farmed eggs. The shells are less fragile (because of more minerals), yolks are bright orange rather than yellow, and the flavor is fuller, more egg-y.

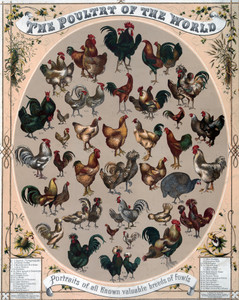

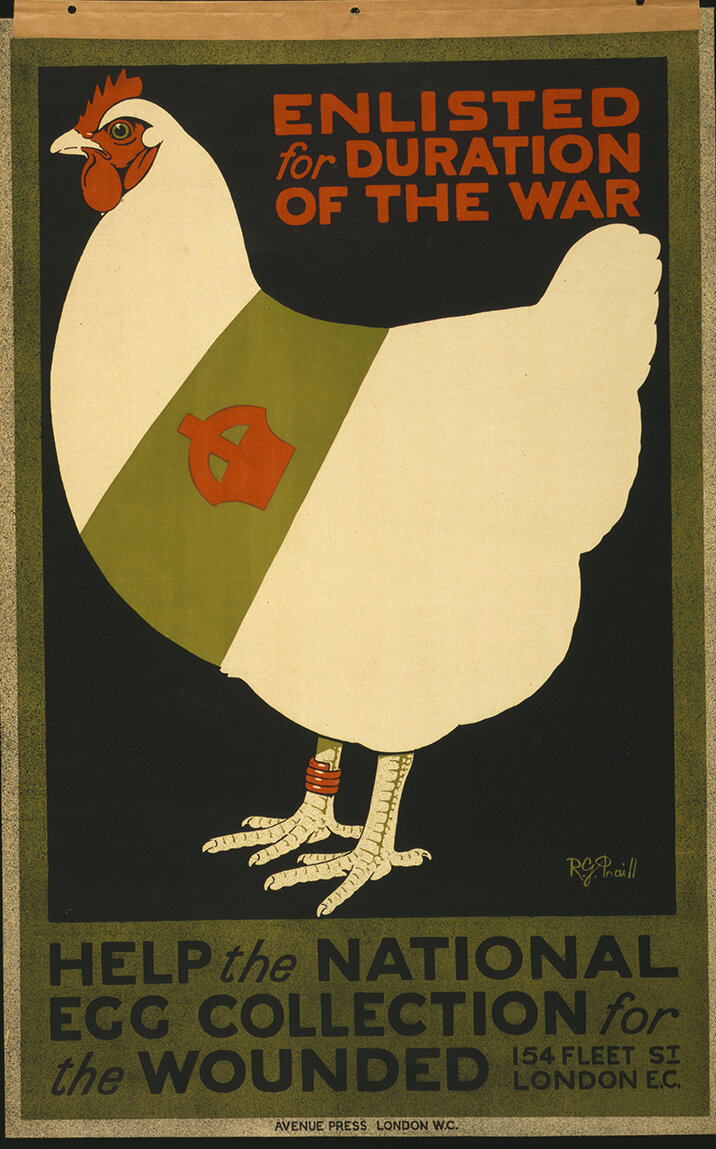

It hasn't been so long since that flavor was the norm. Until the second half of the twentieth century, chicken keeping was common in rural America, and not unusual in towns and cities, where plenty of people, at least in some neighborhoods, kept a few chickens for meat and eggs. In doing so, they were following a worldwide tradition of animal husbandry that developed when the first wild Asian Red junglefowl were domesticated 5,000 or so years ago. In the absence of refrigeration, keeping chickens was the best way of ensuring access to fresh eggs. American farmers kept such breeds as Brahma, Cochin, Plymouth Rock, and Rhode Island Red, all now considered Heritage Breeds by the Livestock Conservancy and threatened with extinction to varying degrees.

Growing up on an Ohio farm in the 1880's, my grandmother was given a bantam chicken to raise. She named it Pip, and cared for it until one day it somehow impaled itself on a fence post. She wept — but that same night, when, plucked and cooked, it was presented to her for supper, she was not so sad that she didn't enjoy the meal. More common now are people like my brother. He keeps a hobby flock of chickens, including Polish Crested, Campine, and Buff Orpington and others chosen for their beauty, hardiness, and temperament. He relishes the eggs his "girls" produce, and he loves them as pets, kissing them occasionally as he holds and strokes them and mourning their deaths when predators attack — and never cooking them for dinner.

Although not everyone would recommend kissing chickens, handling them keeps them tame, and tame chickens are easier to manage. And his chickens (some breeds more than others) seem to return the affection, or at least take a noticeable interest in him beyond expectation of food. But keeping chickens isn't all cuddling and tasty eggs. The predator threat is constant. Foxes, hawks, weasels, and coyotes all appreciate easy pickings. There's a lot of work involved in keeping safe, healthy chickens that goes well beyond the picturesque tasks of collecting eggs and tossing chicken feed each morning.

The daily toil and vigilance required is not for everyone. Old-time chicken owners would probably point out that pictures don't show the hours or the sweat expended on repairing fencing, cleaning coops, or shoveling snow from pens. Also, chickens may live 10-15 years but they don't typically produce many eggs past the age of about 2. Keeping chickens has its attractions, but a dose of realism should be taken to balance nostalgic dreams of producing your own breakfast eggs.