Cloud Chasing Chariots: Early Yosemite Photographers

Posted by Katrina Trepsa on Apr 8th 2020

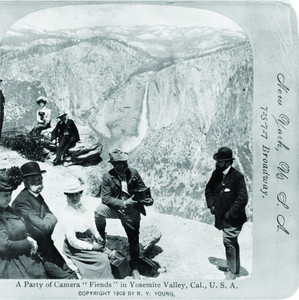

Imagine it’s 1860. You want to capture the clouds over Yosemite. But you don’t just hold your hand above the sky, squint and take a picture. There are no hand-held cameras, no phones, no cars, no GPS. It’s just you, a stagecoach, a twelve-mule pack train, an assistant, and a ton of photographic equipment (literally).

After a two day trip from San Francisco, you reach Yosemite and start maneuvering around the hairpin bends that snake their way up the mountains. At each bump in the road, you worry that your glass plates will crack or break, and that your forty-pound wooden box of a camera will fall apart. If you stop to capture one of the scenic views along the way, you worry that the sun will warp the camera equipment and that the grit kicked up by the mules will stick to the plates as they’re being coated. You worry your mules will run out of steam and leave you to bake in the hot August sun.

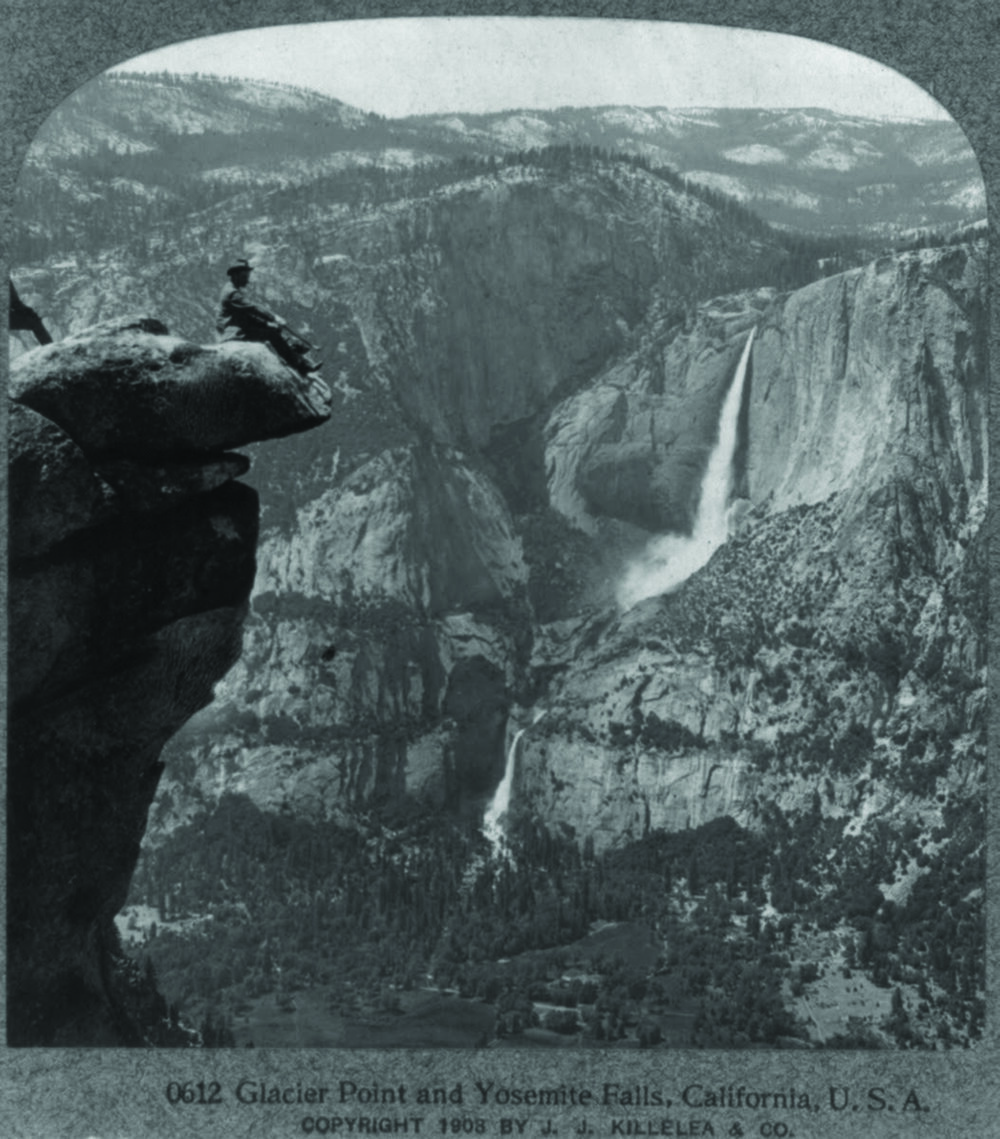

When you reach ten thousand feet above sea level and set up the stagecoach to double as a darkroom, you realize you don’t have any water nearby to wash negatives with. Even though it’s summer, you’re knee deep in snow, so you build a small brush fire to heat some stones and drop them into bucketfuls of snow to make water.

Finally, you can look up and hope that the clouds look picturesque that day.

So why go chasing after clouds? Why not take it all in, the mountains and trees and clouds all at once? Remember that exposure times were so long that skies and moving water came out as flat whites.

George Fiske, one of the earliest masters of capturing clouds, lived in Yosemite year-round, in a studio on the floor of the Valley. When he saw the perfect cloud forming, he would run after it, pushing his wheelbarrow of equipment dubbed the “Cloud Chasing Chariot.” Like other photographers who came to Yosemite, he sold his prints and postcards to tourists who came during the summer season. He had to make a living, after all. Photography was an expensive art.

While Fiske stayed in Yosemite for forty years, Edward Muybridge made two brief yet successful visits that earned him widespread recognition and allowed him to pursue his pioneering work in locomotion photography. In a way, Yosemite was the perfect place to prove himself. He was a daredevil, willing to climb up cliffs that others considered inaccessible and dangle himself (and his equipment) over precipices to get the best shot. He also kept a stacks of cloud and sky negatives on hand and imposed them on the final landscape prints.

The composite nature of even the earliest forms of photography points to a certain artifice inherent in the medium from the very beginning. The predecessor of Photoshop, if you will. The public that bought Fiske and Muybridge’s prints was used to landscape painting and expected sky and stone to come together in seamless harmony. Photographers endured incredible hardships only to erase their efforts from the final product, allowing their viewers to travel to Yosemite without the dust and dirt of the road. These cloud-chasers also secured a lasting legacy; in part because of their work, President Lincoln signed legislation to preserve Yosemite Valley in 1864.