Edward Penfield And The American Poster

Posted by Judith Maas on May 8th 2020

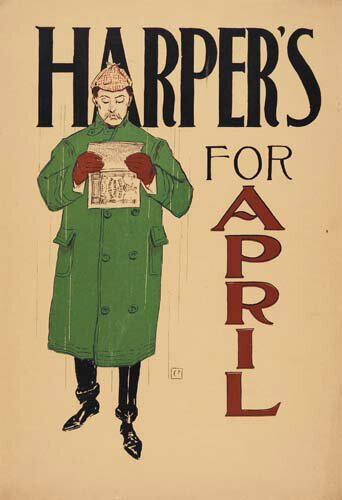

Edward Penfield’s first poster for Harper’s in 1893 shows a man in a green coat absorbed in reading a magazine while being splashed by raindrops; the display type accompanying the figure is as matter-of-fact as can be: “Harper’s for April.” A 1922 article described this spare image as an “epoch-making event,” stating that “[u]ntil the days of Penfield America remained a complete stranger to the poster as a form of artistic expression.”[i] The solitary figure, the flat field of color, the paring away of detail, and the absence of a background were something new. Giving the viewer minimal information, the poster nevertheless tells a story: an April shower will not deter this gentleman from the pleasures of good reading. And in another departure from convention, Penfield initialed his poster, announcing himself as an artist with his own distinct style and raising the stature of the poster form itself.

Posters had been used in the past in America to promote household goods, plays, circuses, minstrel shows, wild west shows, and political events.[ii] During the early nineteenth century, simple posters of one or two colors were made from woodblocks.[iii] By the 1850s and 1860s, lithographic printing companies were employing in-house artists to draw images that technicians would separate into different colors and then transfer onto lithographic stones. The finished work was precise and realistic.[iv] Rather than bear the name of the artist, the posters usually displayed the name of the lithography or printing company. Their purpose was practical: to sell the product and win business for the printer. The style and originality of the posters themselves were not of concern.[v]

Social changes in the years after the Civil War laid the groundwork for a “golden age of illustration.”[vi] Public education, increased literacy, public libraries, and a growing demand for information and entertainment propelled the rise of the illustrated periodical, which in turn provided growing and new businesses in an industrial age with a venue for advertising their products. An expanding railway system and postal service allowed publishers to reach wider audiences, while advances in color printing and photomechanical reproduction improved the quality of illustrations and made their production more efficient and economical.[vii] And the pictures themselves—prints, cartoons, photographs—exerted their own allure, giving readers access to images of contemporary life, from city scenes to the day’s news to fashions.

In November 1890, the Grolier Club of New York City held an exhibition of poster art, popular in France since the 1830s and 1840s. On display were works by such French masters as Jules Chéret, known for his effervescent images of music halls and cabarets, and Eugene Grasset, whose designs incorporated the flowing lines and ornamentation characteristic of Art Nouveau. Nearly overlooked on the occasion were a handful of posters by American artists—these were traditional images, almost photographic in style.[viii] “American posters show little personal impulsion; all are good,” wrote a critic for The Art Amateur. “But it is impossible to tell Matt Morgan’s work from W.J. Morgan’s, or the latter from Thomas’s and Wylie’s.”[ix]

Within a few years, the American poster artist would be obscure and neglected no longer, thanks to a business decision by Harper & Brothers and to the talents of Penfield, the company’s art director. Since the 1880s, magazine publishers had been employing artists to create special illustrated covers for holiday issues, while giving regular issues a standardized treatment—typically, a masthead and a listing of the issue’s contents. In early 1893, Harper & Brothers, pleased by the favorable response to a Grasset design for the 1892 Christmas issue of Harper’s magazine, decided to try an experiment: stocking bookshop windows and newsstands with a new poster each month to advertise the regular issues. Harper’s assigned Penfield the task of designing a poster for its April 1893 issue.

Penfield’s education and travels had exposed him to several of the trends influencing the artists of the era. Born in Brooklyn in 1866, he studied at the Art Students League between 1889 and 1895, under the guidance of George de Forest Brush, who had earlier spent time in Paris working among the Impressionists and had helped to spread the new style back home in America. Penfield himself traveled to Paris in 1892. Through his interest in Impressionism, he would have become familiar with Ukiyo-e, the Japanese prints of the late seventeenth through the early nineteenth centuries and would incorporate into his own work such elements as flat colors, informal poses, and depictions of everyday scenes.[x]

His April 1893 poster inspired other publishers, including Scribner’s, Lippincott, and the Century Company, to follow suit with their own designs. Soon American poster artists were being recognized at home and abroad. Poster exhibitions took place in New York, Boston, and San Francisco. “The advertising poster has within recent years actually soared into the regions of art,” proclaimed Publisher’s Weekly in 1894.[xi] In 1895, the works of Penfield and other Americans were featured in a Paris exhibition, and Scribner’s published a book on the modern poster.[xii] Admirers began assembling their own collections. A full-fledged “poster craze”[xiii] was underway.

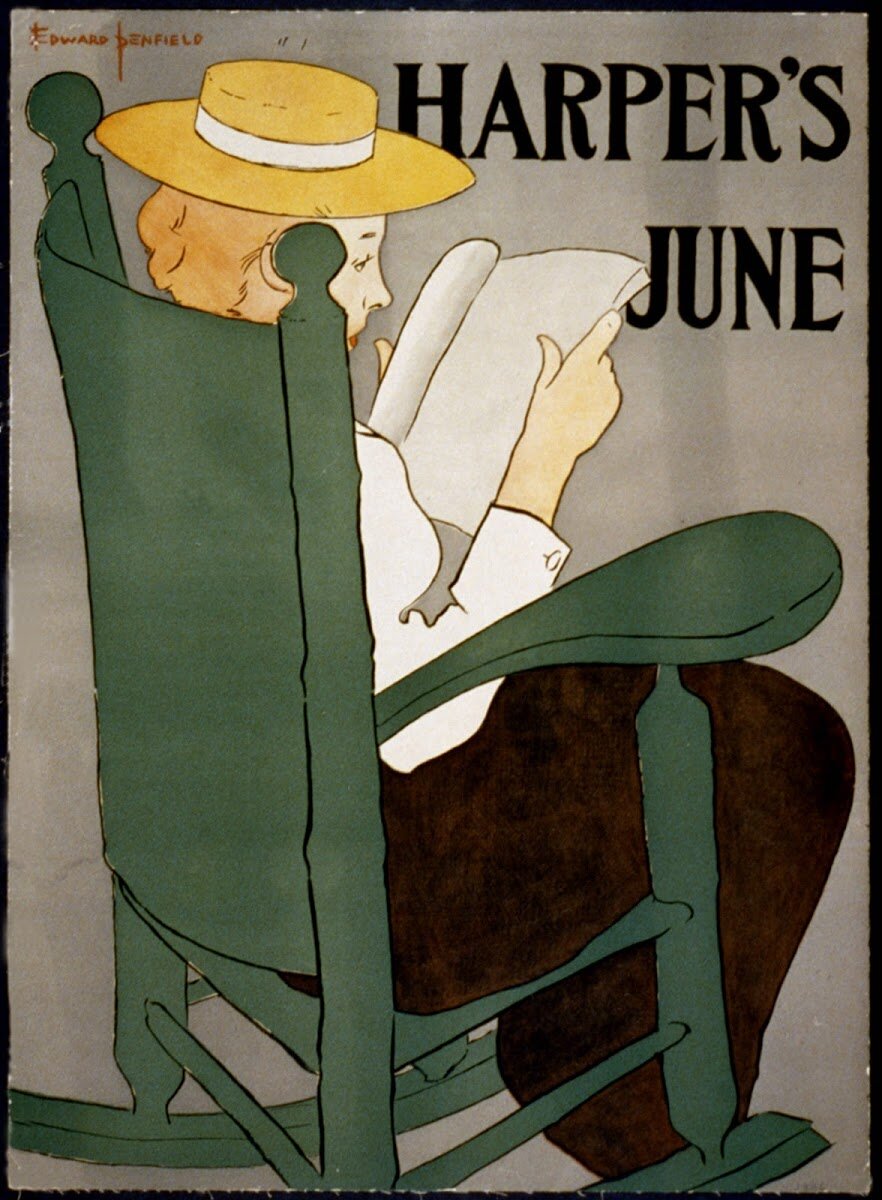

Harper’s was among the more upscale magazines of the day, appealing to educated, middle-class readers and featuring fiction, poetry, reviews, and articles on current events, art, and travel. While other magazines, such as the Century and Scribner’s, had a roster of artists design their posters, Harper’s relied exclusively on Penfield, giving him the chance to experiment with his signature style, to play variations on a theme. His posters feature well-dressed young men and women in casual poses, engaged in enjoyable pursuits—reading, bicycling, golfing, swimming, rowing. Wholly absorbed, often alone or with just one other person, Penfield’s subjects have a cool, detached quality; many look away from the viewer. Sometimes, they float in space, or else a few lines and shapes evoke a backdrop, a room, or a landscape, or a garden. Colors abound. As an animal lover, Penfield liked to show his subjects in the company of cats and dogs, adding a playful touch. The mood is placid and leisurely.

Meant to sell magazines, Penfield’s posters blur the line between commerce and art. In his introduction to Posters in Miniature, an 1896 compilation of images, Penfield offers his view of how a poster should function. In stressing the need for simplicity, he implicitly acknowledges its role as an advertisement—to capture viewers’ attention and make its point: “A poster should tell its story at once—a design that needs study is not a poster…. A poster has to play to the public over the variety stage, so to speak—to come on with a personality of its own and to remain but a few moments.” At the same time, he points out the care and skill it takes to achieve these effects[xiv] and notes the affinity between posters and paintings: “A poster…must have the same qualities that a good painting possesses—color, simplicity, and composition—but must be expressed in a different manner.”

If not the same as a painting, a poster is its own form of imaginative expression, beautiful in its own way, Penfield’s statement suggests. Even as advertisements, Penfield’s posters do not cajole or manipulate. They are pleasing to the eye, quite apart from their utilitarian purpose. Their clarity and economy, sprightly colors, tranquil atmosphere, and the gracefulness of their subjects give pleasure and invite the viewer to linger.

Indeed, during the 1890s, publishers’ posters proved far more successful as artworks valued by collectors than as advertisements—rather like clever ads whose products we don’t remember. Toward the end of the decade magazine publishers began to pursue other means of advertising.[xv] Penfield’s career continued to flourish—he illustrated books, magazines, and calendars; designed promotional materials for such commercial clients as Pierce-Arrow Automobile and the clothier Hart, Schaffner and Marx; and produced popular posters of male athletes for the Beck Engraving Company. During World War I, he turned his skills toward making posters to support the war effort. Beginning in the 1910s and on into the 1920s, Penfield taught at the Art Students League, and in the early 20s served as president of the Society of Illustrators. His work was displayed in exhibitions and publications, including a memorial exhibition by the Society of Illustrators, following his death in 1925.

Penfield’s rain-soaked reader of 1893 helped to legitimize an art form in America; in turn, the poster craze accelerated the development of book jackets and magazine covers[xvi] and helped bring elements of modern art into everyday life. In 1881, long before Penfield began his career, a critic for The Magazine of Art lamented the lack of delight in the lives of working people and offered a prescription: “The fact is, that to reach the people, art must step out of the picture gallery, out of the museum, out of the schoolroom, out of the boudoir, and go into the streets.”[xvii] Gracing shop windows and newsstands with their designs, Penfield and his colleagues answered the call.

[i] Harold R. Willoughby, “Edward Penfield: Father of American Poster Art,” The Poster, 13, Nov. 1, 1922, 21.

[ii] Victor Margolin, American Poster Renaissance (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1975), 17.

[iii] Ibid., 17.

[iv] David Gibson, Designed to Persuade: The Graphic Art of Edward Penfield (Yonkers: Hudson River Museum, 1984), 4-5; Roberta Wong, American Posters of the Nineties (Lunenberg, VT: The Stinehour Press, 1974), 7.

[v] David W. Kiehl, “American Art Posters of the 1890s,” in American Art Posters of the 1890s in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 13.

[vi] Introduction, Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 188, American Book & Magazine Illustrators to 1920 (Gale, 1998), xiii.

[vii] Nancy Finlay, “American Posters and Publishing in the 1890s,” in Kiehl, American Art Posters of the 1890s, 45; Introduction, Dictionary of Literary Biography, xvi; Susan E. Meyer, “American Illustration: A Brief History,.”

[viii] Roberta Wong, American Posters of the Nineties, 7.

[ix] Ibid., 7.

[x] Gibson, Designed to Persuade, 9; Margaret A. Irwin, “Edward Penfield,” in Dictionary of Literary Biography, 243.

[xi] Quoted in Gibson, Designed to Persuade, 4.

[xii] Margolin, American Poster Renaissance, 20.

[xiii] Ibid., 19.

[xiv] See Gibson, Designed to Persuade, 11, for an account by Penfield’s son Walker of his father’s working methods.

[xv] Finlay, “American Posters,” 46.

[xvi] Ibid., 46; Wong, American Posters, 10.

[xvii] Wong, American Posters, 7.