On Nostalgia - An Essay

By Michael J. Simpson, MA History

SYNOPSIS: This essay presents an exploration of the evolution of the concept of nostalgia from its inception in the late 17th century to its modern interpretation in the 21st century. By chronicling the path of nostalgia from chronic ailment to evolutionary benefit, it explores nostalgia and its juxtaposition within American history. The commercialization and institutionalization of nostalgia has helped to manifest a unique American identity.

(This article may be freely relinked as long as the author and source are cited.)

PART 1: NOSTALGIA: A SENTIMENTAL LONGING FOR THE PAST

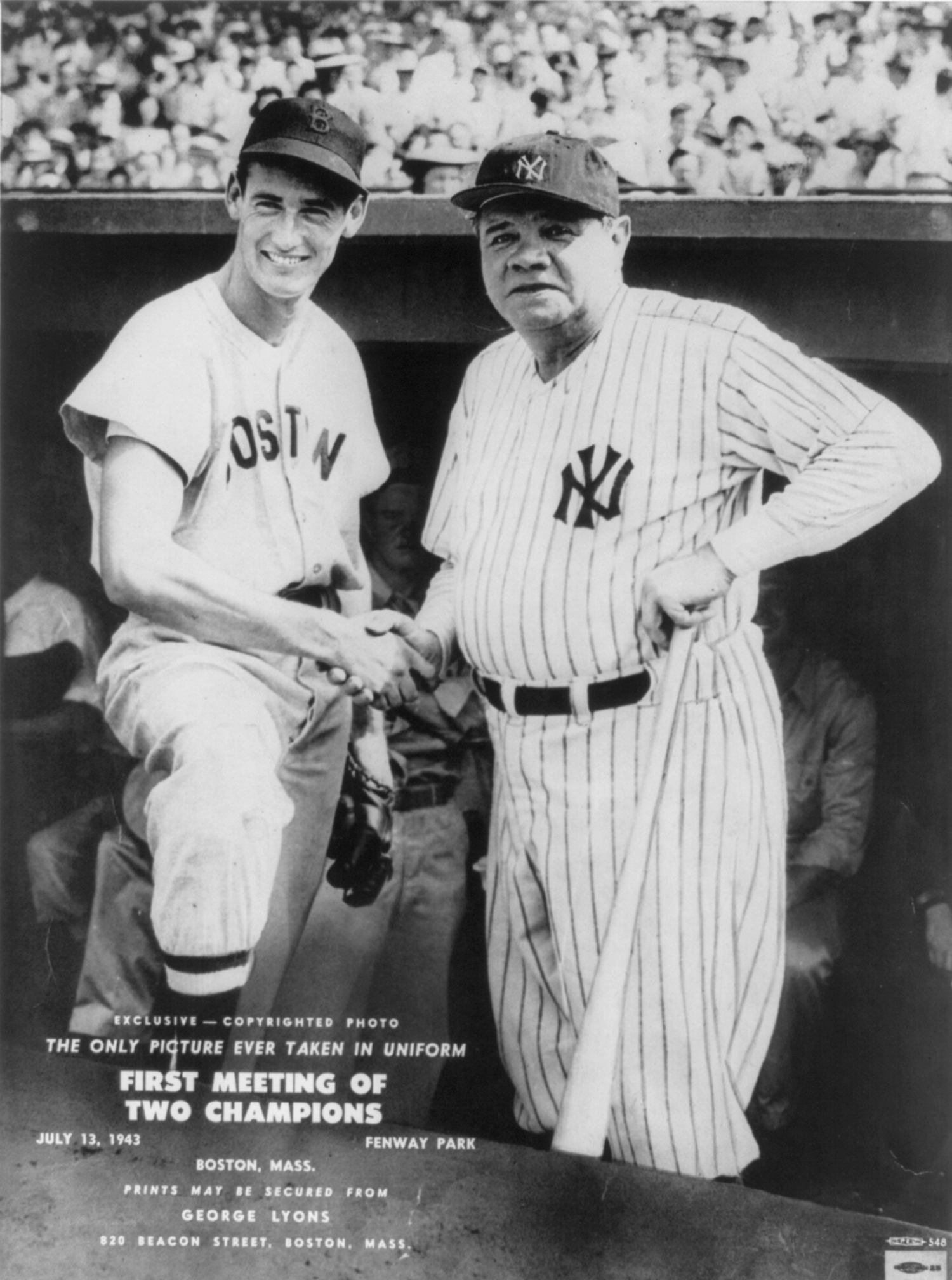

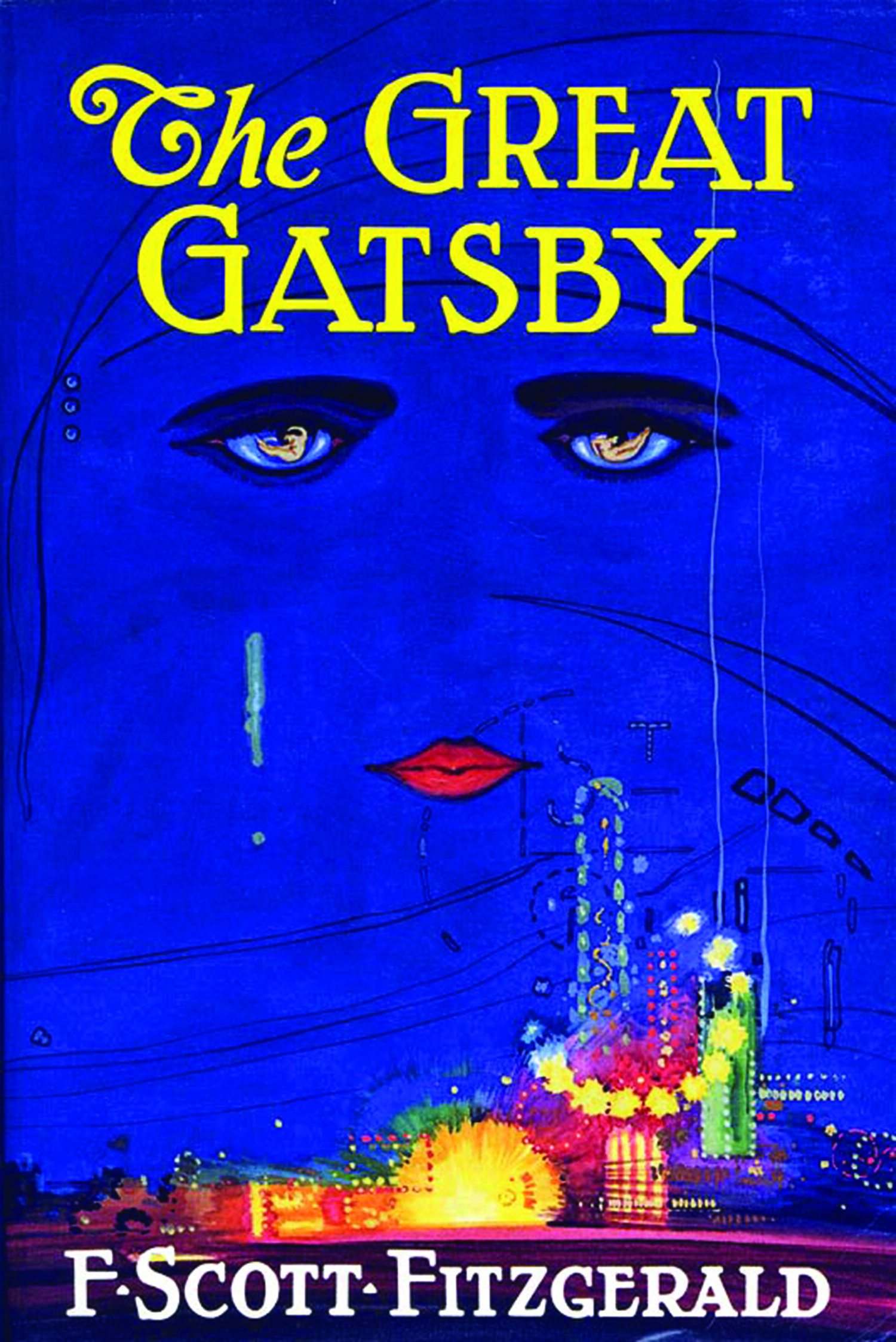

"Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch our arms farther… So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby [1]

A woman walks down the street in the late afternoon and passes someone speaking in Spanish. She is transported back in time to the months she spent traveling through Spain. She can smell the scents of tapas bars and see light casting shadows on juxtaposed buildings, and she imagines herself sipping an espresso in a cafe—as if she's truly there. By experiencing this bout of nostalgia, however accurate or not, she has fostered a feeling of social connectedness with those around her. By searching for similarities in her own life experience, her brain has found an instinctual connection to strangers strolling through the neighborhood.

A bite of chocolate may remind her of her grandmother's kitchen, a smell of cologne of her high school love. These experiences are the brain's attempt to find common threads. Connecting one's own life experiences with those one is experiencing in that moment brings the beholder closer to those around them. Over time, the mind may forget less important details. As a result, our nostalgic inferences often reflect a past that we create just as much as we remember. It is an effort by the brain to ground an individual, to place their senses in a succession of smells and sights experienced over time. A seemingly powerful but harmless emotion, nostalgia hasn't always been thought of as something so benign.

NOSTALGIA: THE DISEASE

Once thought of as a curable disease no different than influenza, the term nostalgia was coined by Johannes Hofer in his 1688 dissertation at the University of Basel. Stemming from the ancient Greek nostos—returning home and algos—pain, or longing, Hofer wrote his study after examining cases of Swiss soldiers' ailments on the battlefield.[2] Often serving their duty in landscapes much different than their homes in the Alps, the soldiers yearned for the mountain peaks and crisp air of their homelands.

Attributed by some to be caused by both the changing atmospheric conditions and the constant clanging of cowbells in the ears of the Swiss farmers, it was such a problem in some companies that the whistling of traditional songs sung by Alpine herdsmen was strictly prohibited, for fear of early onset nostalgia.[3] Historically, nostalgia was seen as a 'disease of the people', often afflicting soldiers and sailors traveling far from home.[4] Others saw it as an 'immigrant psychosis' that affected country folk moving from the sparsely populated hinterland to the multitudinous cities of the modern era.[5] Symptoms included melancholy, insomnia, anorexia, weakness and palpitations of the heart, and though Hofer recommended both leeches and opium to cure nostalgia, the most effective remedy was simply what the body craved: a return home.[6]

HISTORY OF AMERICAN NOSTALGIA

At first, many thought that Americans were impermeable to nostalgia because it was such a young nation. Customarily, it was thought of as an exclusively Swiss ailment.[7] But by the time of the Civil War, American doctors were quick to diagnose soldiers with the affliction. Union Army surgeon De Witt C. Peters wrote in 1863 that nostalgia was “a mild type of insanity, caused by disappointment and a continuous longing for home”.[8] As time progressed, so did our conceptions of disease, nostalgia in particular. The advent of germ theory caused the medical definition of nostalgia to become obsolete. And although it was no longer a fitting subject for field medics or medical doctors, it became adamantly pursued by psychologists, therapists, and, later, businessmen of the day.

The paradigm shift was significant because it demonstrated a societal change in the perception of the ailment. Nostalgia had shifted from an illness which could be dealt with on a personal level to an emotion that should instead be dealt with in the public sphere. Following the Civil War, and the subsequent Reconstruction Era and Gilded Age, Americans were searching desperately for stable ground to stand on. Concepts of modernity and progress, and political and economic flux, often came hand-in-hand with a contempt for tradition, the time bygone, and an equivalent void that incited a deep sense of homelessness and a yearning for the past.[9]

As the 19th century came to an end, the craze surrounding American nostalgia was expanding. In this regard, nostalgia worked as a 'slowing mechanism', an evolutionary adaptation to be used by citizens when they felt obsolete in this ever-progression of cultural structures.[10] The massive gap between the rich and the poor deepened into the 20th century, and the advancement of the wealthy often caused those less privileged to feel left behind with all the progress. They yearned for something to ground them in a common origin, a common set of roots in a still adolescent nation. This mentality intensified with the realization that nostalgia could be commercialized and sold. Nostalgia had thus shifted from that which was once a personal and medical, to something that became more emotional and public, with strong aspects of romantic nationalism and globalization.[11]

* * *

PART 2: THE EARLY COMMERCIALIZATION OF NOSTALGIA

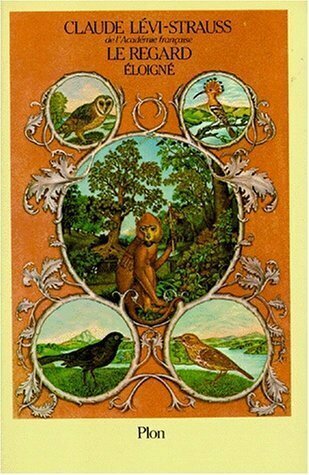

“When objects that traditional taste judges beautiful become too rare and expensive for small wallets, then previously scorned items surface and provide the people who acquire the satisfaction of a somewhat different order—not so much aesthetic as mystical and, one might say, religious. … One surrounds oneself with these objects not because they are beautiful, but because, since beauty has become inaccessible to all but the very rich, they offer, in its place, a sacred character...”

—Claude Levi-Strauss, The View From Afar [1]

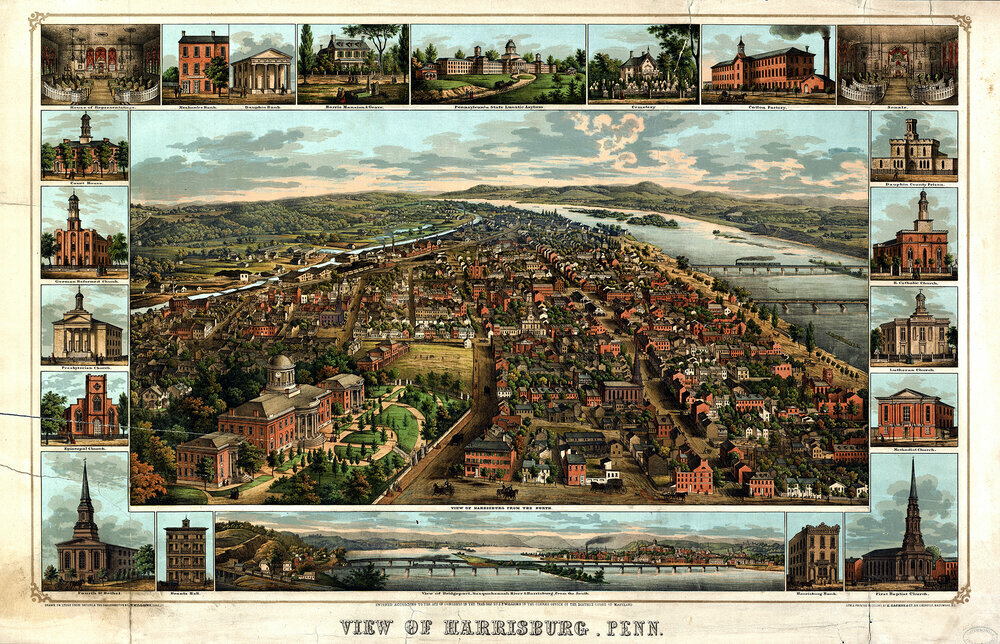

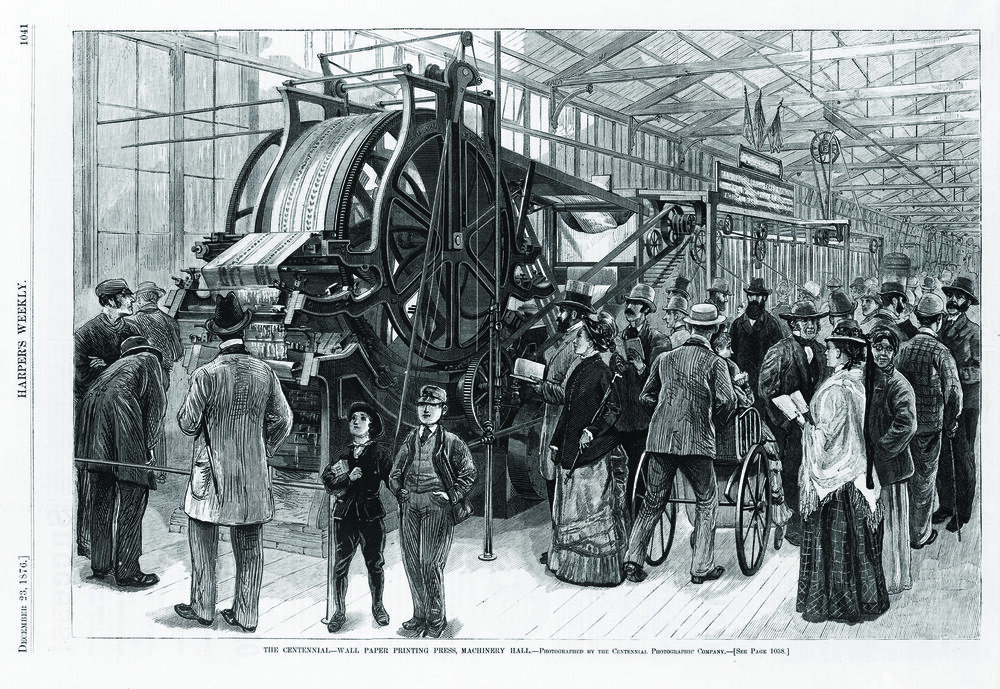

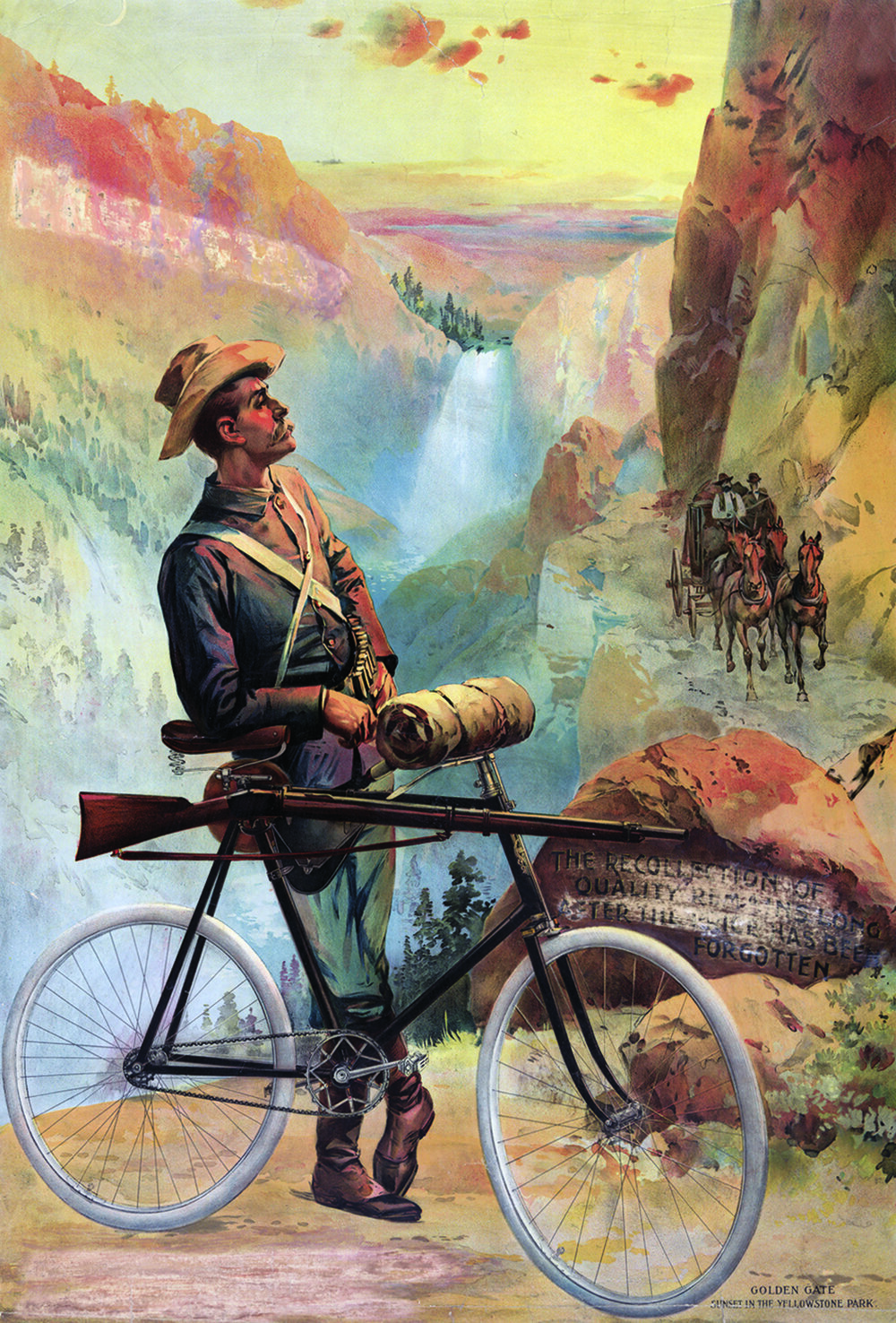

The age of commercialized nostalgia proliferated with the help of drastic technological advancements in photography, printmaking and book publishing. These advancements combined to create a perfect storm of easily accessible and manufactured products to be marketed to not only institutions like museums and libraries, but also, for the first time, ordinary citizens. The craze for nostalgic appeal had created a brand new 'memory industry'.[2] What was once a seemingly harmless yearning for home had quickly become an overwhelmingly economic attempt to find, or even idealize, common cultural roots.[3] This new quest for a common identity was not simply an innocent vision by workers yearning to be included in the national narrative, but was also a manufactured and designed re-creation of a past that could be 'purchased by anyone, for the right price'.[4]

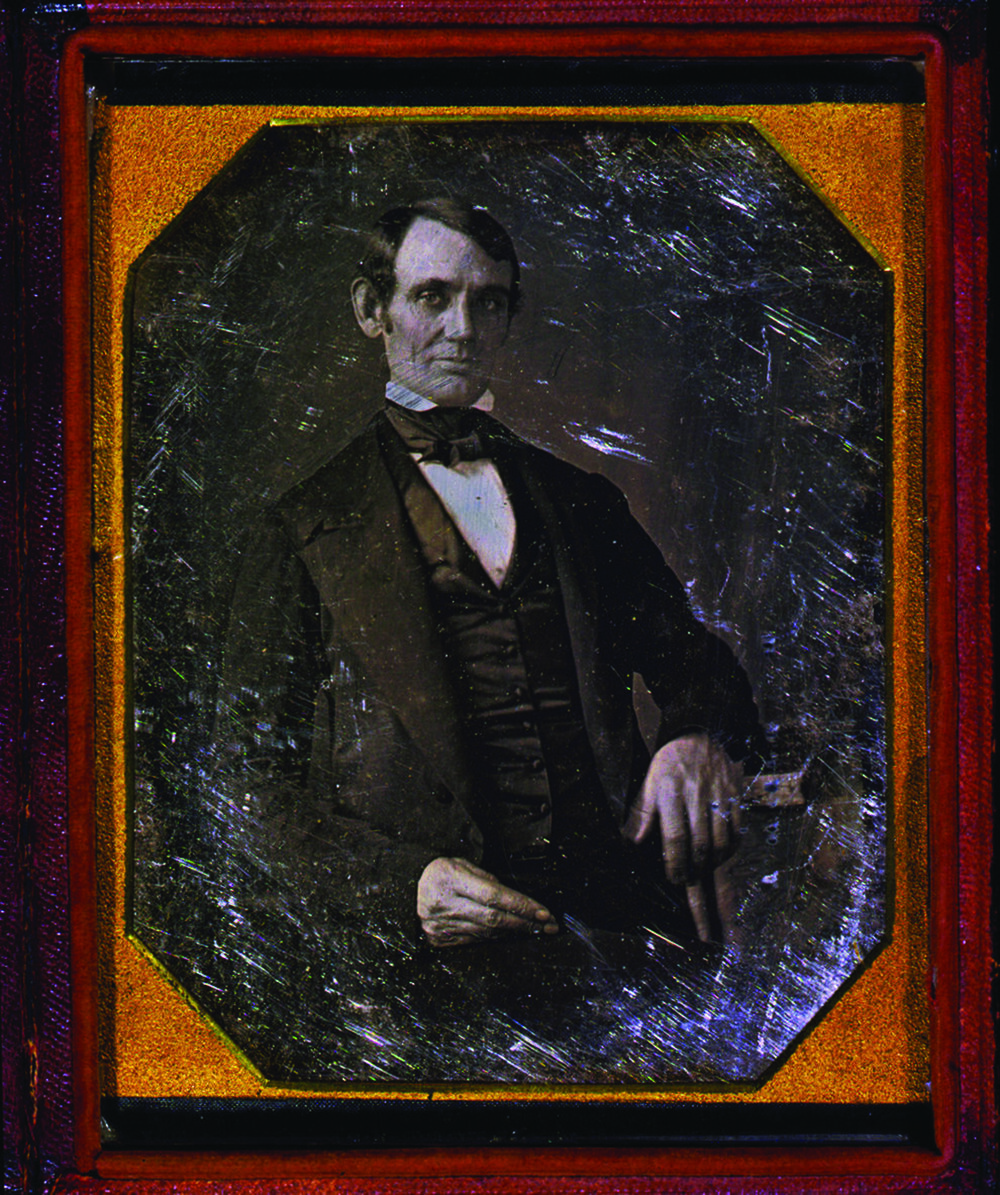

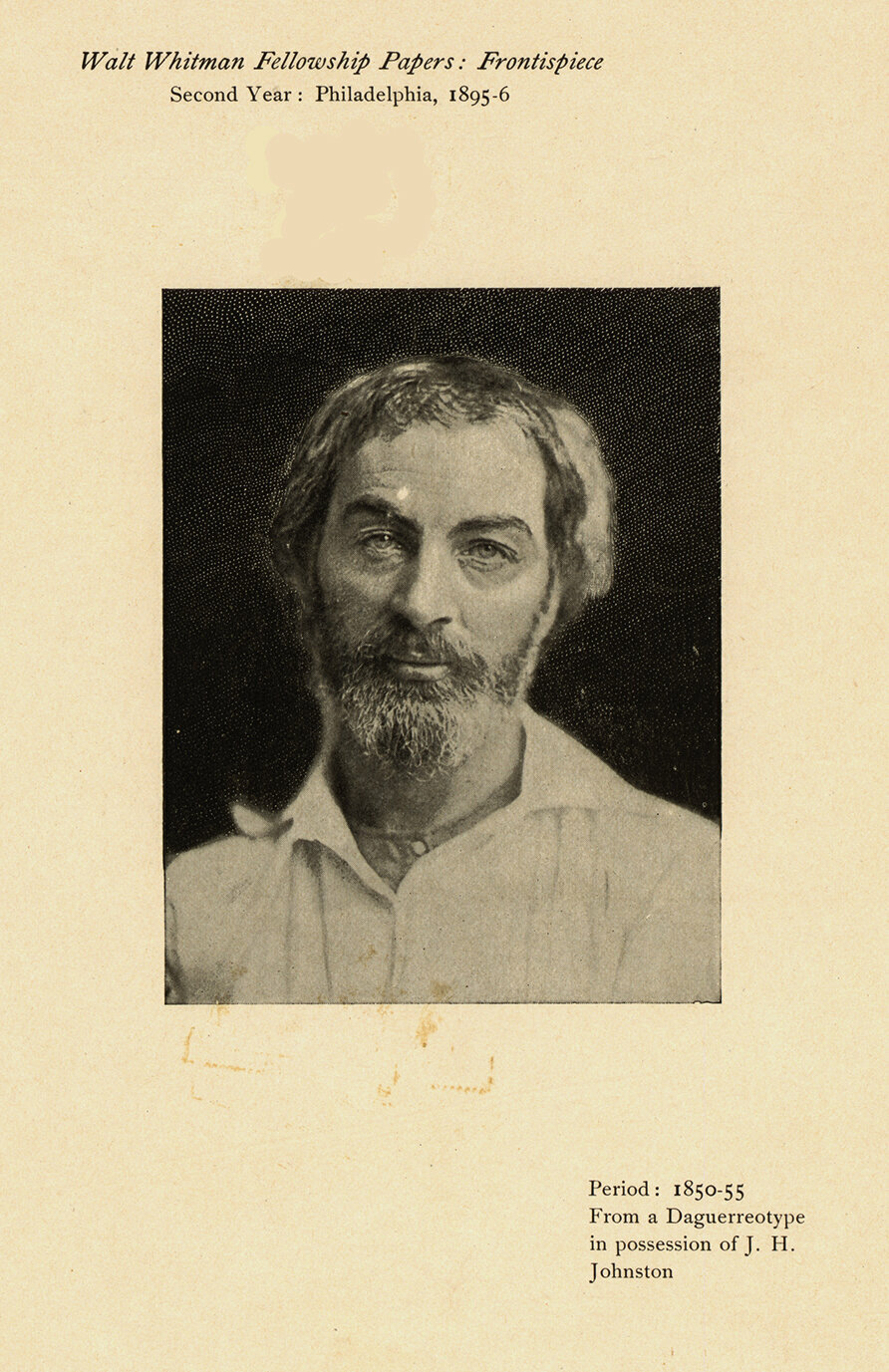

Just imagine the current state of nostalgia without the photograph. In 1839, following the introduction of a new method of developing photographs known as the daguerreotype, the medium quickly advanced to unprecedented levels. Unlike other art forms, photography offered a glimpse of the past in a completely novel way. It allowed Americans to feel a more immediate connection to the people and places of their own past. S.D. Chrostowska writes that “the paramount historical role of photography in the production and marketability of nostalgia should not go unremarked”.[5] Soon the photograph was commonplace, a necessary measure needed to record events for posterity. It was also part of the burgeoning memory industry, and without it the modern mentality may have never existed.

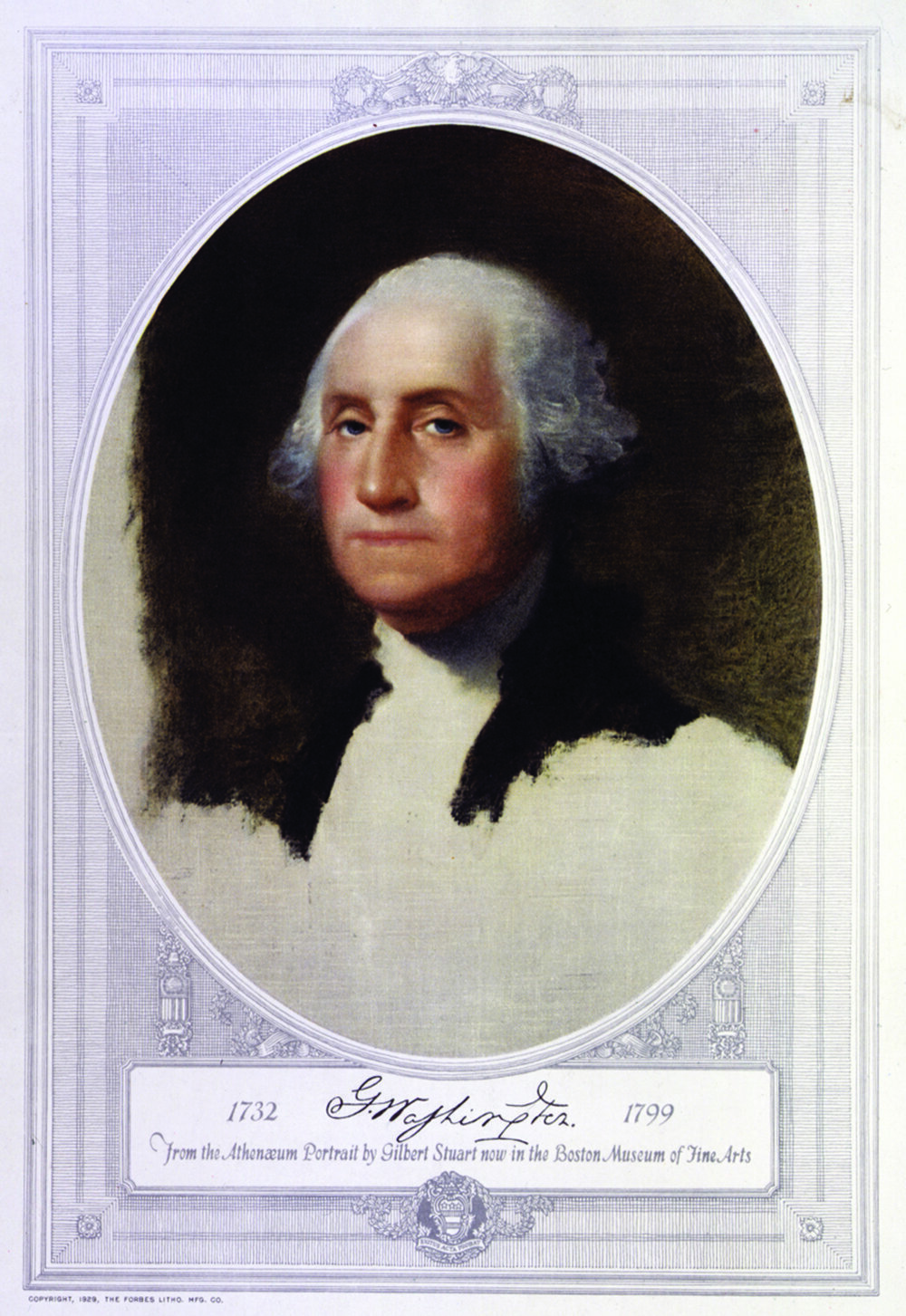

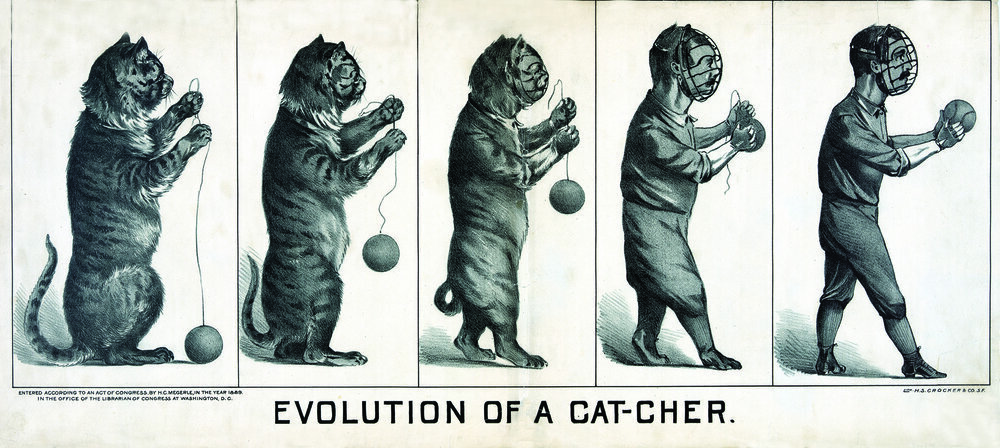

Advancements in printing in the 1830s, like the substitution of steel for copper as a primary medium, once again allowed works of art that had once only been available to the privileged classes more affordable for ordinary citizens.[6] In the early years of the American republic, portrait prints were published of only the most famous and eminent men of the era. With these advancements, allowing for cheaper printing, subject matter for prints became democratized, allowing for more images of citizens of other classes. The portrait prints of the eminent did not cease, however. One of the most proliferated images was that of George Washington, which was often hung on the walls of many American homes, regardless of class. Here began the creation and concretizing of an American cultural identity, complete with its own myths, heroes, and bouts of nostalgia.[7]

Books, and the nascent beginning of an American-published genre of literature, may have played an integral role in not only the molding of an American cultural identity, but also its counterpart; the commercialization of nostalgia. For ages, the country's most printed book had been the Bible. America's first Bible was printed by John Eliot, written in both English and Algonquian, and published in 1661. The Bible continued to be the nation's most printed book into the late 18th century, when the Aitken Bible, printed in 1781 in Philadelphia, became the 'Bible of the Revolution' after receiving an endorsement from the Continental Congress. This wasn’t the first attempt of a new nation to form a collective identity under this holy book. But it did reflect a larger American nostalgia for the old world and its culture, connecting the uprising of the American Revolution with the rebellions of the Bible. This thinking demonstrates the way that nostalgia and American identity have intertwined since the country's inception.

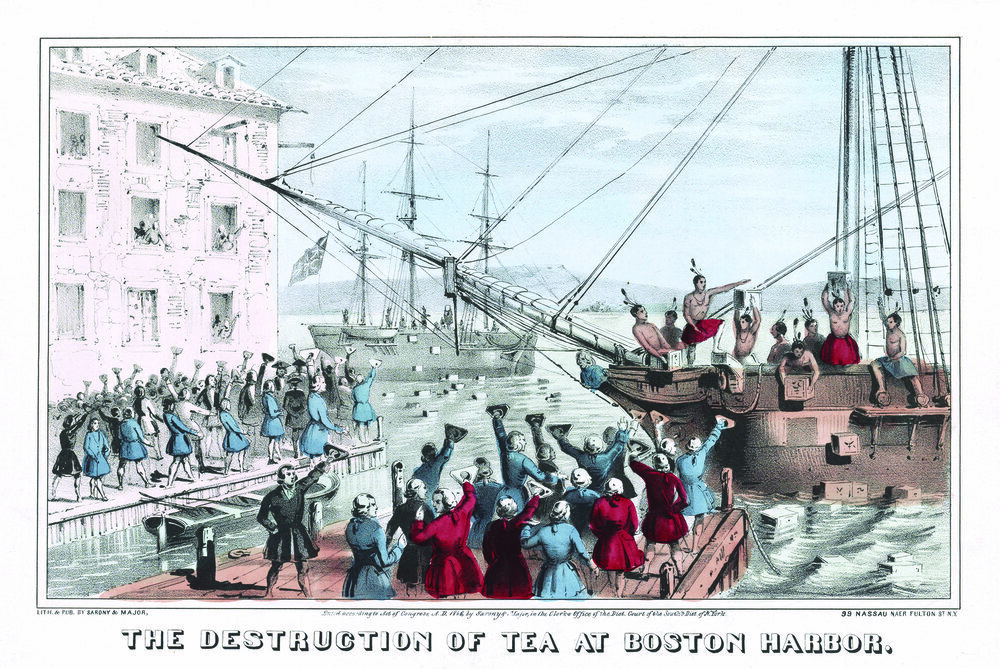

A NEW AMERICAN IDENTITY

For those rebellious colonists during the Revolutionary Era, creating an American identity became a form of patriotic nationalism, an attempt to find a common bond in a nascent nation. As time progressed, colonists found that bond in the image of the Native American. The most renowned example of this was the Boston Tea Party. Held in 1773, protestors costumed themselves in Algonquian accouterments as protection against Loyalist retribution. By this time, the image of the Native American was beginning to become a widely used as a symbol of resistance to British authority.[8]

Named after 17th century Lenape leader Tamanend, fraternal organizations like the Tammany Society, founded in 1786, epitomized this cultural appropriation: seizing the image of the native to signify a multi-ethnic American identity. In the early colonial period, holidays already existed for full-blooded Irish and French American. The feast days of St. Patrick and St. Denis served as the traditional days to celebrate those heritages. However, if one was not a full-blooded Irish or French immigrant, he or she would not be able to participate in these celebrations. Tammany Day, celebrated on the first of May, would be the only option for multi-ethnic Americans, as an event where mixed heritages were revered as a distinctive aspect of American identity.

For Americans rebels, native imagery reflected their unconscious desires and represented a source of new ideas void of the antiquated notions of class and autocratic governments that defined their homelands.[9] It was a reflection backwards to the time when the nation was primarily inhabited by indigenous peoples again demonstrated an early American nostalgia. Only this time it was a yearning for a time lost, void of overarching taxation from foreign governments and frivolous ideas of class. As the American nation matured so too did its technologies soon allowing for new allotments in the dissemination of culture, memory and nostalgia.

The advancements in bookmaking and other technologies in the early 19th century paved the way for what would become a burgeoning American memory industry. The replacement of leather to cover books with cloth, combined with a change in binding techniques, completely transformed the outward appearance of books. This shift also allowed for a division of labor, which lead to hiring unskilled, low-wage workers to perform these formerly expensive operations and subsequently to the manufacturing of a cheaper product. All of the sudden books were no longer drab pieces of paper encased in animal skin. Instead, they were affordable, vibrant with color, and had 'seductive, eye-catching displays'. James Green states that these innovations were “the greatest in book marketing since the colonial period”.[10]

By the 1840s, further advancements in paper-making, typesetting and printing machinery, like steam-powered printing presses, made books even cheaper to print and thus even more accessible for readers. Combined with new means of transportation from railroads and steamboats, distribution ballooned. Elizabeth Barnes writes that in the four decades from 1789 to 1829 “roughly two hundred works of American fiction were published. But by the 1840s, that number had increased to eight hundred.”[11]

CULTURE IN A NEW AMERICAN NATION

Printed material had quickly developed from a means to disseminate information and religious texts to a major medium of entertainment, education and political will. Sandra Zagarell writes that early American books had become “instrumental in forging an American identity, a national culture.”[12] American authors born in the early 1800s were the first generation of this new country, and they were dead set on forging and establishing this national culture. More often than not, they succeeded.

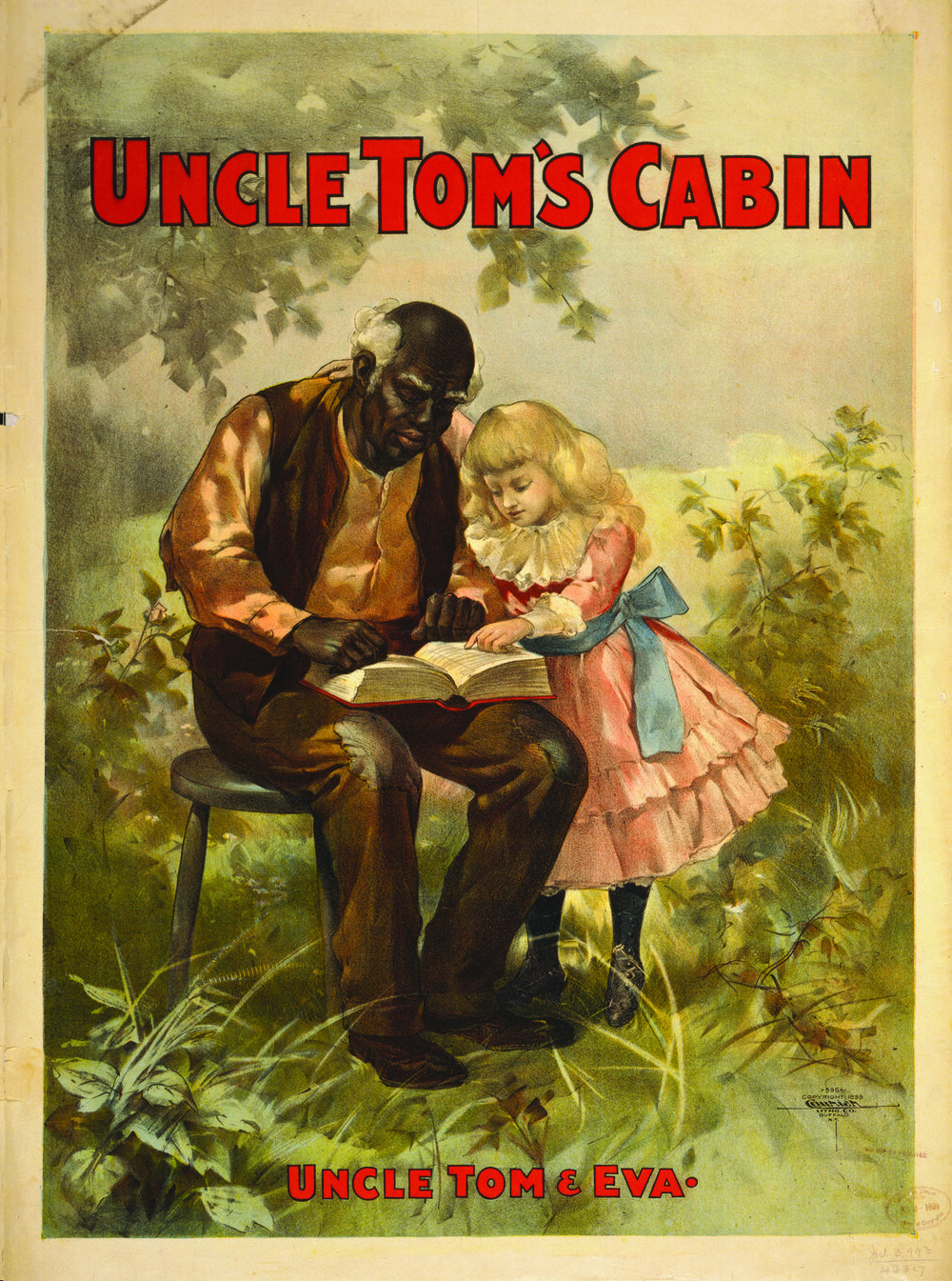

The democratization of the printing industry not only revolutionized the accessibility of the medium for ordinary citizens, but also allowed for formerly prohibited citizens, namely women, to participate in the process for the first time. Women of the early 19th century America saw literature as an opportunity for them to become 'agents of nationhood' charging ahead to shape America in order to reflect their own ideals and dreams. Harriet Beecher Stowe, born in 1811 in Connecticut, actively participated in the national conversation surrounding abolitionism. Uncle Tom's Cabin, written by Stowe and published in 1852, became the second best-selling book of the 19th century, falling behind only the Bible. The book is recognized by many as laying the groundwork for a national discussion on the abolition of slavery, if not raising the issue altogether. Two years later, in 1854, Henry David Thoreau would publish Walden, which similarly lamented about the excesses of a material society, particularly the institution of slavery.

This generation of authors also included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Longfellow, and Frederick Douglass. With works like Washington Irving's Knickerbocker's History of New York and James Fenimore Cooper's Last of the Mohicans setting the tone, these authors worked to create a distinct American identity, one with its own culture and mythology. Folk heroes emerged from the past. Characters like Molly Pitcher, John Henry, and Johnny Appleseed, who were all based on real historical figures, gained mythical status with the retelling of their stories.

Later generations like that of Mark Twain and W.E.B. Du Bois continued the work of concretizing a distinctly national and American literature, by surgically deconstructing the larger zeitgeists of the day and interlaying them within their own works. These publishers, printers and authors helped to effectively craft a unified American identity, one that defined itself by interweaving nostalgic notions of the past and strove to find common links and traditions. Books like F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby suggest that the spirit of this era was defined by the reaching backwards in time. While the Jazz Age of the 1920s is often considered to be a period of joy, discovery and wonder at a new age of progress and modernity, Fitzgerald's novel implies that this period of time was actually an attempt to recreate the past. Whether or not it was accurate did not seem to matter.

National cultural works like this manifest powerful symbols from our collective pasts to help construct, deconstruct and reconstruct our national identities.[13] Americans became increasingly worried that they would soon become obsolete in the cultural changes that epitomized the late 19th century in the United States. Transformations of culture during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era of the 20th century caused Americans to look backward in time, not just for personal reasons, but as a civic duty, to construct a national identity and common tradition that would act as a means to ground citizens to their time and place during these times of momentous and dynamic change.[14]

* * *

PART 3: THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF NOSTALGIA

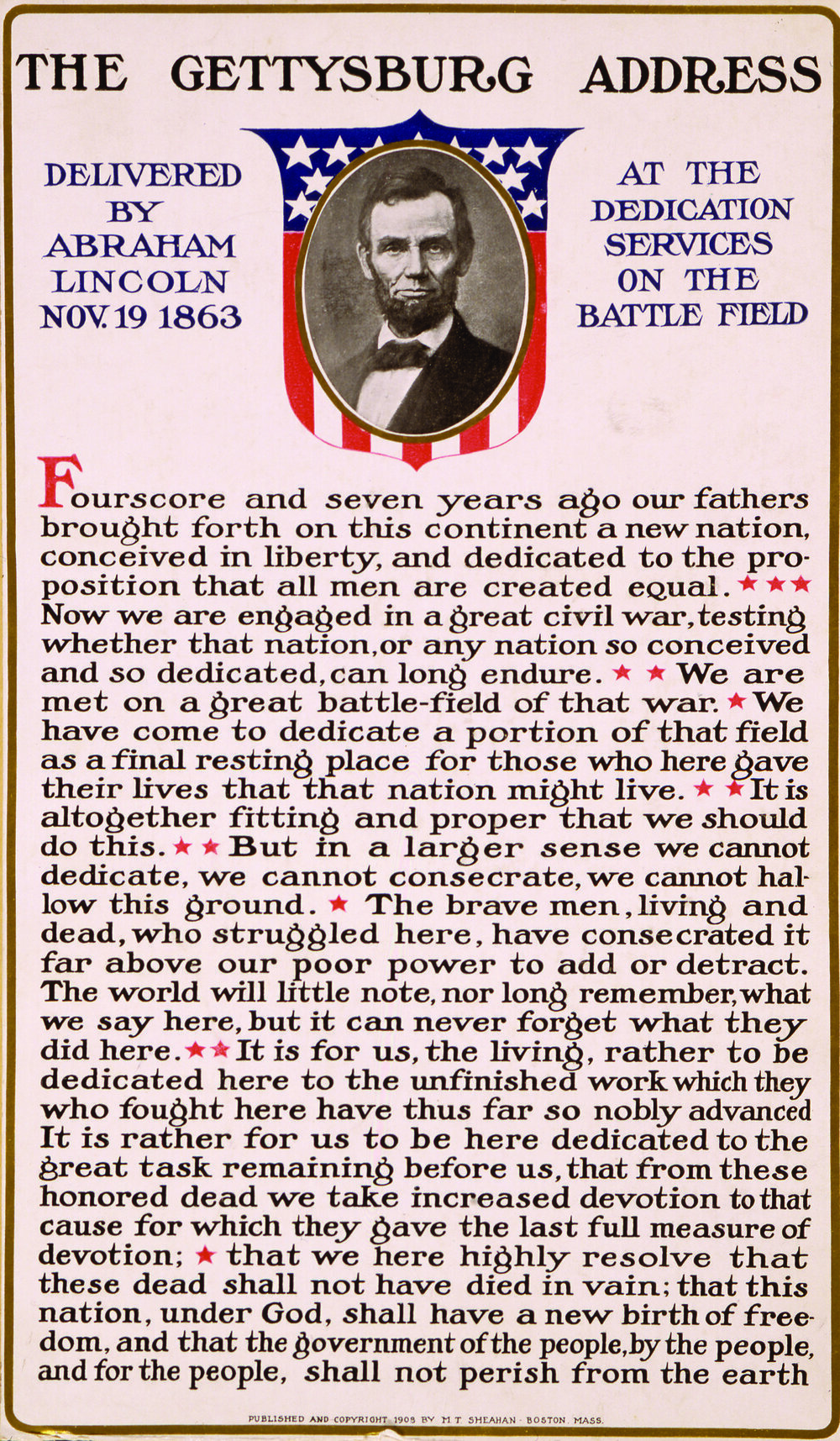

Towards the end of the 19th century, following one of our nation's most divisive conflicts, the campaign to unite Americans around a common identity and culture strengthened and soon took a new form – that of nationally recognized holidays. With the nation at a pivotal period in its development, this was an attempt to build a notion of community on a national scale by effectively institutionalizing nostalgia. Though the holiday had first been informally “declared” by George Washington, President Abraham Lincoln, in his Proclamation of Thanksgiving in 1863, called for the observance of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in order to “heal the wounds of the nation”. Two months later, Lincoln would deliver his Gettysburg Address which began with his most famous and nostalgic of utterances: “Four score and seven years ago…”

In 1870, both Christmas and Independence Day became federally recognized holidays. Halloween also emerged during this time, brought from the shores of England, Ireland and Scotland to America by the arriving masses of immigrants.[1] Often called 'Harvest Home' by Europeans, this festival has been celebrated since antiquity. The ancient festival had ceremonies of death and rebirth, with aspects that were associated with the devil, ghosts and spirits.[2] Potentially nostalgic for the traditions of the homeland, these practices would be incorporated into the American holiday of Halloween. Celebrated around the time of the final crop for the year, Halloween also coincided with similar Native American festivals surrounding the harvest.

This juxtaposition harkens back to the earlier appropriations of folk traditions of Native Americans and Europeans to find common bonds to create unified, multi-ethnic American identities. Thomas Morton's 1637 May Day revelry, which combined European folk symbolism in the maypole with Native Americans ideas of fertility and spring harvest festivals, may have been the first of this tradition. These celebrations represented attempts to connect through a common heritage and tradition as Americans instead of distinct groups of Europeans, Africans or Native Americans.

There was also a commercial aspect to all of this celebration. Each of these holidays; Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Independence Day have all since developed from attempts by Americans to create common bonds and traditions together as a nation, to being aggressively co-opted by commercialism. From candy and costumes, to presents and fireworks, these holidays are no longer defined simply by a bringing together of families and traditions. Instead, they focus on who can consume and spend the most. Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, published in 1843, represents the angst surrounding these folk traditions turned commercial frenzies. Its main character, Ebenezer Scrooge, struggles to understand the 'true meaning' of the holiday, only to be reminded by physical representations of his nostalgia of the past, present and future.

As Americans struggled to find common roots among those with different ethnic backgrounds, these holidays helped to bring people together. The closing of the 19th century brought about an assimilation and solidification of race and ethnic-based identities. 'Europeans', 'Africans' and 'Indians' were all molded into conglomerate representations. Before then, a man from York would never refer to himself as an Englishman, let alone as a European, and would rarely find common cause with, say, an Italian. Although there were many cases for an 'African' identity as far back as the Revolutionary Era, it became more common by this point in time. Now, it would be more likely that a man from San Domingo would refer to himself as an African, or that a Pequot would call himself an Indian. Ethnicities in America slowly began to become molded together based on their similar cultural roots. At this time, as Dickinson Bruce writes, “most institutions created by blacks … chose to use the word African in their titles as a way of defining both their character and their distinctiveness.”[3] These 'pan-identities' emerged as the first step of creating a unified American identity, though the tendencies towards an exclusively white national identity would still continue well into the 20th century.[4]

At this point in American history, old ideas of natural cycles of change were being uprooted and replaced with concepts of progress and modernity. The past was somewhat absent from this mentality. Modern inventions like the railroad and steamboat allowed people to travel farther away from home than they ever had before. Communication advancements like the telegraph and a national postal service allowed people to communicate across distances rapidly, at an unprecedented rate. In the 19th century, the United States Postal Service was stronger than ever, and in the 1890s, with the advent of rural home delivery of mail, nostalgia had never come easier to the average American.

The first postcards went on sale in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1873. Once home delivery of mail was introduced in 1893, the postcard quickly helped to form the epitome of American nostalgia and its craze. According to the Postmaster General, in 1875 107 million postcards were issued. By 1910, 700 million would be mailed out in that single year. Journalists referred to the craze as 'postcard-itis' and once again nostalgia had taken up the mantle of an ailment. As a result, the first two decades of the 20th century are considered to be the golden age of postcards.[5] Over time, the United States government would continue to play an integral role in institutionalizing an American identity. With the creation of national holidays like Thanksgiving, Christmas and Independence Day, the government actively worked to foster common traditions amongst its citizens. The United States Postal Service, and its home delivery of mail, connected Americans like never before.

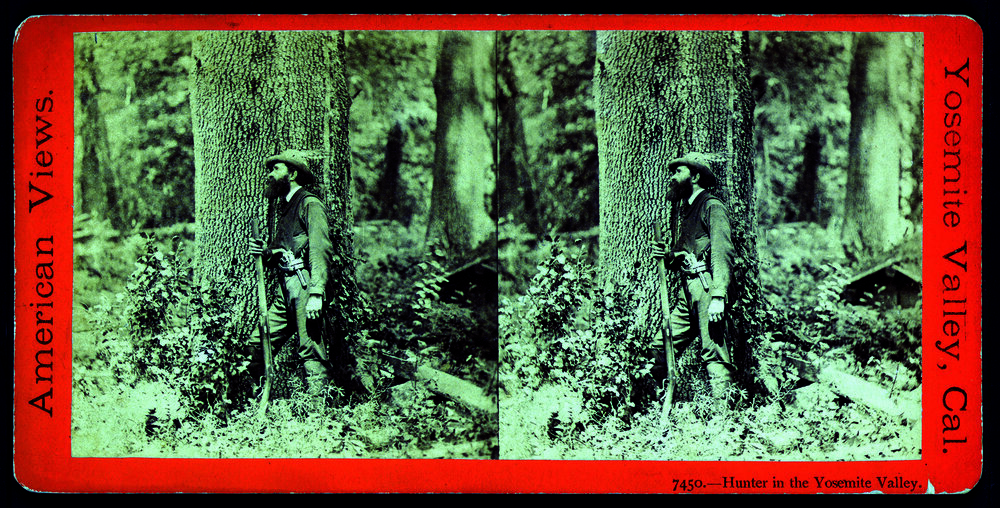

In 1864, President Lincoln signed an Act of Congress that designated a portion of the Yosemite Valley to be used for as a public park for recreation. This was the first of many national parks to be designated by the federal government. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed a bill that would establish the National Park Service which further worked to preserve vast expanses of land, sometimes occupied, sometimes not. Freezing these vast expanses of land in time, and preventing them from exposure to the epidemic of progress and modernization afflicting the nation, was yet another facet of our national nostalgia. Preserving Yosemite in its state of nature, void of buildings and garbage dumps, would allow citizens to reflect on what they believed the nation once was; a vast, and open space, untouched by human hands. As S.D. Chrostowska writes; “the more distant a past, the better it can serve as a playground for the commercially bound imagination.”[6]

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

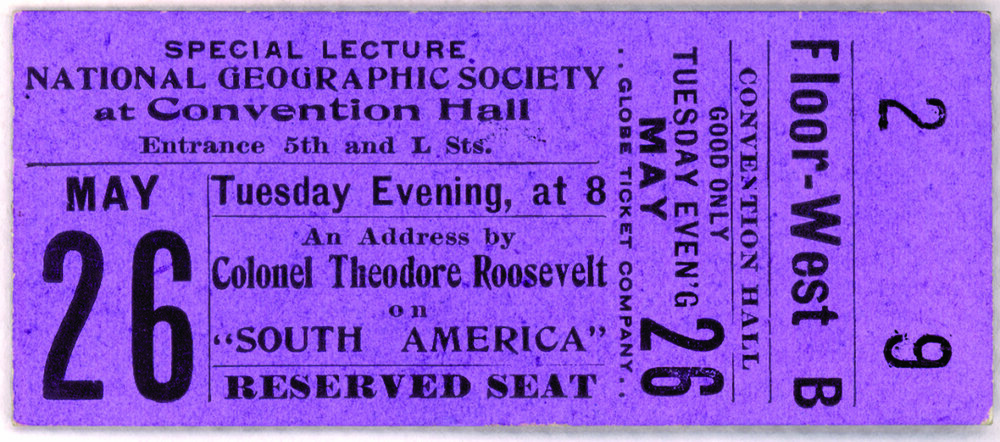

Not all of the institutionalization of nostalgia was performed by the government. In 1888, the National Geographic Society was founded with a mission dedicated to 'the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge'.[7] Created outside the for-profit memory industry, the journal that eventually became the National Geographic magazine set out to create a sense of a 'complex connectivity among nations and cultures'.[8] Over time, this connectivity developed into the creation of a mythic American past. According to Stephanie Hawkins; “readers were participants not just in science but in an ongoing narrative of American nationhood”.[9] Founded during a time that the nation and the culture surrounding it was rapidly advancing, publications like National Geographic assisted in a 'national negotiation' of identities, both mythic and factual.[10]

What was once a small journal circulated among members of the society, quickly advanced to have over ten million subscribers in the next century. During that century, the magazine served as the nexus that Americans turned to when questioning their own sense of nationhood and national identity. The 'civic performance' acted out by National Geographic is one that works to find commonalities within citizens of the nation, but also with citizens of the world. This 'collective membership in global networks' is one that would perpetuate with the advance of the Internet and the World Wide Web.[11] Created roughly a century before the Internet, this publication stands as a testament to the ability of the memory industry to actively coalesce and form a national culture and identity.

When constructing these national narratives of identity, Americans worked desperately to 'rope off, sanction and harden its myths', and anything that didn’t fit within this preferential framework often fell to the wayside.[12] Such is the case when imagining national parks as time capsules of what the nation once was, as these spaces were never truly empty (at least not within the last few centuries) and to remember them as such is far from factual. Americans had constructed and stewarded this image of the past just as much as the Native Americans had tended the lands in the years prior to their incursion. In attempts to combine pasts together into common traditions, homogenization often cast aside the particulars, and instead elevated familiar similarities. Additionally, this assimilation became xenophobic, and exposed drastic differences from itself as un-emblematic of an American identity.[13]

Eventually, Americans began to realize that idolizing the past was much different than venerating the present. The past had to be constructed and created through rituals like holidays, and symbolized in relics and mementos like photographs, books and postcards.[14] An anxiety soon developed surrounding a lapse of memory of the past. Memory, after all, was not infallible. An institutionalized past could alleviate this anxiety, and would slowly begin to affect the nation's concepts of culture. Enter the public institutions of museums, historical societies and libraries, structures developed by the incentive behind preserving a national history and a personal narrative for the country.

THE SMITHSONIAN

Birthed in 1835 following the death of British scientist James Smithson, the Smithsonian was formed as a result of a bequest included in Smithson's will. The institution that would become known as the Smithsonian would also become a paradigmatic example of a nationalized compendium of culture. Preserving everything from archaeological artifacts to movie props, the museums of the Smithsonian share the same mission as the National Geographic Society. Established in the will for the collection to be used for the 'increase and diffusion of knowledge', the Smithsonian works to construct and mold an American identity, formed by the myths and cultural artifacts of the past. It is ironic that James Smithson had never travelled to the United States, yet his estate's collection, valued at over $500,000 at the time of donation, would create one of the largest cultural museums and research complexes in the country.[15]

Following the establishment of the museum's official capacity as a national institution by President James Polk in 1846, the Smithsonian's acclaim as an American cultural compendium continued to grow. This popularity was just another testament to the nation's love of nostalgia and the increasing marketability of the memory industry. By 2014, over 28 million unique visits were totaled by the Smithsonian's museums.[16] The vast amounts of visitors to this museum and its institutions even to this day demonstrate the major role that they play in manufacturing the concepts of national traditions and identities. The gift stores and retail shops operated by the Smithsonian bring in an estimated 27 million dollar profit each year, and over 150 million dollars in actual revenue.[17] These retail operations contribute the most funds out of any other Smithsonian program, further testament to the strength and importance of nostalgia and the memory industry in creating a national culture.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Museums and other public institutions like the Smithsonian revolutionized nostalgia, creating the first instances in American history where nostalgia could be both institutionalized, manufactured and ultimately, preserved. By cataloging, restoring and reproducing cultural artifacts, these institutions came to help form the definition of America's past and heritage and simultaneously increased the commodification of and demand for nostalgia. By, as S.D. Chrostowska puts it, 'rerouting the stream of history and erasing its scars, these museums have had the unique ability to actively manufacture American nostalgia and sell it exclusively.'[18]

Officially begun in 1800 by an Act of Congress signed by President John Adams, what would become the Library of Congress had a very slow beginning. In 1814, following an attack by the British on the newly established capital in Washington, D.C., a great majority of the eight hundred books in the library were destroyed in a massive fire. Immediately afterwards, former President Thomas Jefferson donated a portion of his personal library to replace the lost books. His donation included over three thousand books, effectively tripling the size of the collection in a single donation. In 1865, Congress began to appropriate funds to create an official national library of the United States. As a part of the continuing effort to create a unified American identity, the construction of the Library of Congress was just another means to institutionalize nostalgia.

THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE

The Copyright Law of 1870, which required all copyright applicants to submit copies of their work to the Library of Congress, made sure that the development of American identity and institutionalized nostalgia would develop in parallel. By 1897, with over eight hundred thousand volumes, the Library had quickly become the largest in the country, and the Copyright Office, overwhelmed by the amount of works registered and deposited in the previous two decades, branched off to become its own, separate department.

Many often saw nostalgia as a 'departure from the past', but its institutionalization helped to create a somewhat more accurate depiction.[19] With a national library dedicated to collecting all literature produced in the country, it reflected an attempt at an all-inclusive history, a new kind of more accurate nostalgia, one based in documented facts rather than simply personal memories. In addition, a state compendium like the Library of Congress worked to foster social connectedness by creating a common national mythos on an unprecedented scale.

Capitalizing on bygone era books whose copyright status has since expired, a newer industry has emerged over the past several decades which further evidences of the marketability of nostalgia. Companies like Arcadia Publishing and Applewood Books have published thousands of titles, not only out-of-print books but also local histories accompanied by images free from copyright due to their age. These publishers have filled a niche created by the most recent trend in the commercialization of nostalgia – the digitization of our past in yet another effort to bring readers and researchers closer to their community, neighbors and past.[20] Publishers like these add to the social connectedness of nostalgia as well by bringing back local and lost histories in an effort to forge common bonds among their readers.

* * *

PART 4: THE DIGITIZATION OF NOSTALGIA

Fast forward to the modern era and the Library of Congress of today houses over twenty million cataloged books included within over one hundred sixty million total items. In 1989, a pilot project aptly titled American Memory laid the foundation for the National Digital Library Program, which began in 1995. This program works to digitize selected collections of the Library of Congress that emphasize the complex history of an American cultural heritage. Not only serving to digitize books, pamphlets and manuscripts, the Digital Library Program also works extensively to collect images that reflected the unique and vast holdings of the Library of Congress. By 2000, the program surpassed its goal of scanning over five million items and making them accessible online.

By institutionalizing American memory, the program works to firmly establish a national culture based on the writings, images and symbols from our collective past. The program also represents a shift from the analog to the digital. Commercialized nostalgia is inherently connected to this idea of progress. For some, the emergence of the Internet spelled the end of nostalgia, burying the concept deep beneath the ground, and leaving behind the easy accessibility of the history, culture and images necessary to be nostalgic.[1] Ironically, as Svetlana Boym writes, “progress didn't cure nostalgia, but exacerbated it”. In the face of seemingly unstoppable globalization, stronger attachments to local histories and cultures developed, further compounding the ailment.[2]

Much like the advancements in bookmaking and photography, the Internet has helped pushed the memory industry in a direction it had never been before. Ambitious projects like the Digital Library Program, working to digitize the American memory, prove to what extent this invention has taken nostalgia to an entirely new level. Websites developed by private organization like Ancestry.com and Archive.org, which work to make genealogical information and other nostalgic material available to those with a modem connection, also represent a portion of those inspired by the accessibility of the Internet.

THE GOOGLE BOOKS LIBRARY PROJECT

Even in the Internet era the institutionalization of nostalgia is not solely a governmental operation. Inspired by the Library of Congress's project, in 2004 Google announced the creation of the Google Books Library Project. In a short span of time, the Library of Congress quickly had some competition in the realm of digital libraries. By partnering with Harvard University, the University of Michigan, the New York Public Library, Oxford University and Stanford University, this project worked to combine and digitize the collections of these libraries, estimated at about fifteen million volumes.[3] The goal of this project was similar to that of the National Digital Library Program, and the Smithsonian and the National Geographic Society before it -- to proliferate the access and diffusion of knowledge.

By creating an exhaustive and searchable database of digitized works, the Google Books Library Project hopes to help readers explore previously inaccessible books, much like the program at the Library of Congress. In 2005, in light of the similarities of the programs (and aside from one being a publicly funded program and the other a privately funded one), Google donated three million dollars to the Library of Congress to help them with their Digital Library Program.[4] This fell in line with Google's mission to help in organizing the world's information and making it universally accessible. In accomplishing this, Google essentially created a global compendium of culture, from which we can draw from to create a global mythos, a global identity, and a global nostalgia.

Far ahead of its competitors (often thanks to its connections in education and sheer capital available from its parent corporation), the Google Books Library Project is quickly becoming an invaluable research tool of our past.[5] With future partnerships on the horizon, there is no end to the amount of work that could be digitized and made searchable, and to the bounds of nostalgic inquiry. What often took researchers months and months of traveling to check out and read valuable books in libraries, pouring over voluminous pages and indexes to find key words, now can be completed in a single search online from the comfort of one's own home. At its core, the process will soon revolutionize scholarly work and the world around it much like the print making processes of the late 18th century. Not only will access to these previously inaccessible books be enlightening for researchers and other students of history, but it will also provide new avenues of profit by reintroducing demand for books that had for years been resting on library shelves.[6]

THE BUSINESS OF EBAY

Megan Garber writes, “Nostalgia, at its most basic level, requires access to memories—and there is, of course, no better archive than the Internet.”[7] And nostalgia will be forever bound to the flow of capital. The 'confluence of nostalgia and capitalism' has no better example than the birth of eBay.[8] Here, the potential for profit, which feeds off of the nation's craving for nostalgia, is unlimited. Never before has access to the memory industry (and, in particular, the objects, mementos and keepsakes of our collective past) been so extensive. Founded in a living room in September of 1995 by Pierre Omidyar, the mythic beginning of eBay surrounds the website's mission to create an interactive online space to sell Pez dispensers. With single dispensers being sold for thousands of dollars, and conventions held nationwide to trade and sell these candy machines, this product epitomizes the growth of nostalgia in the form of collectible items that have personal value and connectivity to one’s past. With its purpose to facilitate the auctioning and sale of these kinds of items by ordinary citizens operating on a computer in their homes, the website's popularity skyrocketed. In the entire year of 1996 they hosted an impressive 250,000 auctions. In just the month of January 1997 the site hosted an unprecedented two million auctions.[9]

In 1998, Omidyar hired former DreamWorks and Hasbro executive Meg Whitman who used her business experience to create a different vision for the company than just selling products. Instead, she wanted eBay to be a company focused on the 'business of connecting people'. What was different about eBay was that it allowed users to sell to each other, rather than just buying from a major retailer. Once again there was a democratization of the memory industry.[10] By focusing on connecting people rather than selling products, eBay highlighted the most important part of nostalgia: social connectedness.

Because their business soon was booming, eBay saw many competitors try to emulate their success. Major companies like Amazon are even reaching out to the former giants of memory, antique auctioneers like Sotheby's, to try to get a small piece of the action surrounding the business of nostalgia.[11] However, eBay was too far ahead with its pioneering business model. Its model focused entirely on connecting people, the ever-expanding community of eBay sellers, rather than perpetuating the traditional retail structure that had defined other facets of the memory industry.[12]

The Internet, and websites on it like eBay, have substantially impacted the trade of America's past.[13] People soon realized that they had more in common than they previously thought, and over 100 million people quickly learned that they could trust a complete stranger to sell them items online. The impact of federal holidays, national parks and postcards to foster social connectedness and feelings of nostalgia pales in comparison to the social impact of eBay.[14] What used to take collectors considerable amounts of time and money, visiting garage sales and antique malls throughout the country, now could be easily accessed from the comfort of one's own home. With the logistics of collecting facilitated, the ease with which a collector could accumulate a qualified collection moved exponentially.[15] What once may have taken a lifetime to find can now be done with just a few week’s time and a mailing address. The market of the Internet, and eBay with it, is vast and expansive, unlike anything the world of nostalgia or memory industry had ever seen before.[16]

Collectors aren't the only people who have benefited from the connectedness promoted by eBay. Because rare historical items do well on the Internet, auction websites have quickly become an apt tool for researchers conducting unique archival research.[17] Local markets like town and city historical societies now have access to not only spread their history globally, but to recall those artifacts that have since left their locale. In this same sense, researchers, much like collectors, often live on small budgets and cannot afford to travel the entire country searching for that one particular prized piece. Instead, they can conduct a few searches on eBay, find what they are looking for, and have it delivered to their doorstep.

With the advent of websites like eBay, institutions like museums and historical societies can now more easily construct the nostalgia of their communities. Historical artifacts that were once considered scarce were now available in larger quantities on the Internet. Museum collections now have the ability to expand quickly and cheaply with purchases made online. The Internet has created massive economic centers or marketplaces through websites like eBay where access to American nostalgia has developed at an unprecedented level. With that access becoming faster and easier than ever, technology had once again transformed the memory industry.

ANCESTRY.COM

First started by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 1990s, the website that would eventually become Ancestry.com equally created a research tool of historic significance and means of creating more social connectedness.[18] Since the website's launch in 1996, Ancestry.com has quickly grown in the last twenty years to represent the digital online presence of genealogy. With revenue of $225 million in 2009, their income has ballooned to $620 million in 2014.[19] Literally connecting families in a way they hadn't before, online genealogical websites quickly began the task of creating a 'global tree', or physical map of social connectedness, creating a newly connected genealogical universe unlike anything ever encountered before.[20]

Much like eBay and Google Books, Ancestry.com has quickly become an important tool for historical researchers, archivists and professional genealogists. Like collectors and researchers, genealogists rarely have piles of money to spend following their family lines backwards in time from historical society to town hall to cemetery, all around the country. These researchers can instead focus their capital on website subscriptions and payments for downloads.[21] Genealogical websites like Ancestry have worked tirelessly to digitize entire national censuses and make them searchable. In 2002, it took the company almost a year to digitize and make searchable the census Federal Census of 1930, but by 2012, when the Federal Census of 1940 was released to the public, it was digitized and made searchable in just four months.[22]

Digitization projects like Ancestry.com and Google Books have helped to make the mammoth tasks often imposed upon historians and genealogists much simpler and easier to accomplish.[23] Now at the height of its popularity, Ancestry.com has not only monopolized the online genealogical industry, but also that of personal DNA testing, something that takes personal nostalgia to a whole new level.[24] Now with more than two million subscribers, sixteen billion records and seventy million individual family trees, the website has connected people and family unlike ever before, making over eight billion connections between users' trees.[25] As Howard Bybee writes; “It is safe to say that without the richness of Ancestry.com databases and its dedication to family history research, the genealogical universe would be impoverished.”[26]

SNAPSHOTS OF THE PAST

Established institutions like the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, websites like eBay and Ancestry, and initiatives like the Digital Library Program and the Google Books Library Project are all striving to preserve a national archive of culture and create a more developed and inclusive perspective on American history. Snapshots of the Past, a recent addition to this effort, hopes to continue and extend the archiving work of these companies, making historical images even more accessible to ordinary citizens around the country and around the globe. Like eBay in 1998, James Lantos started his company in his living room. Founded in 2001, it was first inspired by the nostalgia he experienced while conducting family genealogical research. His company soon became one of the first to make available as prints some of the rare collections of images held at the Library of Congress.[27]

Early on, Snapshots of the Past recognized the huge interest in historical objects that might be available from source materials found in libraries. The ever expanding archives of the Library of Congress have long been inaccessible to ordinary citizens and restricted only to librarians, researchers and visitors with special permission. Snapshots came to understand how it could combine technological advances in offset printing in order to open up these materials to people who wished to own a copy of the Library’s rare maps, photos or other artwork. By mastering a relatively new technological processes in digital, archival printing, working with the scanned digital imagery being produced by National Digital Library Program, and by hand cataloging and categorizing the Library’s many digital galleries and collections, Lantos and his company have joined a long line of innovators working to democratize nostalgia, and make it more accessible.[28] In this way, the company’s mission is similar in scope to that of mass-production lithographers of the early 1800s.

Instead of selling only one image, however, like the ubiquitous George Washington print, Snapshots of the Past now allows people to choose from over one hundred thousand of the Library of Congress’s most beautiful works. Driven by a passion for sharing documented history, websites like Snapshots of the Past, Google Books and Ancestry.com are unique in an industry that focuses primarily on profit. At Snapshots, each image offers information collected from the Library's archive, including the date, photographer and location. By allowing people to search vast quantities of historical information, from out of print books to historical images to historical government census data, Snapshots and others hope to further expand the institutionalization of our national and historical archives by making them more accessible to a common audience.[29]

* * *

PART 5: NOSTALGIA AS AN EVOLUTIONARY BENEFIT

Once solely pursued by doctors and medics in the 17th and 18th centuries, then developed further by historians, politicians, advertisers and other businessmen in the 19th and 20th centuries, the affliction of nostalgia finally returned to the realm of medicine in the 21st century, studied by psychologists once again.[1] Up until this point, most of the research conducted on nostalgia surrounded the field of advertising and consumer psychology. This research indicated that certain product styles that were popular during one's youth would subsequently influence them for the rest of their lives.[2] Though previously studied by medics and surgeons like Hofer and Peters, psychology professor Constantine Sedikides is the most recent doctor from within the profession to carry the torch of the study of nostalgia.

His work strives to change the perception of nostalgia. Once perceived as a disease and a psychiatric disorder, Sedikides believes nostalgia is a “predominately positive, self-reliant and social emotion serving key psychological functions”. [3] One of those psychological functions is a fostering of social connectedness. A possible evolutionary adaptation that favors social groups over an individualist lifestyle, this emotion is a fundamental one that helps to prolong the existence of the beholder. By finding common bonds with strangers outside of kin groups, an individual will have a broader access to resources like food, shelter and protection from predators or enemies, which generally prolongs lifespan. Sedikides proposes that nostalgia revives previously dormant relationships that strengthen social bonds and “renders accessible positive relational knowledge structures”.[4]

Other research conducted by Sedikides's colleague Tim Wildschut has found that feelings of nostalgia actually have a physical reaction, often in terms of a warming sensation. Psychologists believe that the reaction may be an evolutionary defense mechanism meant to temporarily protect us from the cold and other elements. Wildschut writes that “nostalgia serves a homeostatic function, allowing the mental simulation of previously enjoyed states, including states of bodily comfort”. [5] This research, when paired with other studies that highlight the social connectedness aspect of nostalgia, once again demonstrate the importance behind the emotion.

It seems, after all, that nostalgia was far from a debilitating ailment, but was instead a fundamental human strength. As modern psychologists like Sedikides and Wildschut began to study nostalgia a bit further, it became clear that it was indeed an important evolutionary adaptation, one that elevates self-esteem, alleviates existential threat, boosts optimism, sparks inspiration and even fosters creativity. [6] On a social level, nostalgia emerges as a means to strengthen communal bonds. Once evoked, nostalgia creates a sense of social connectedness and compels people to be more generous to strangers, and more tolerant of outsiders.[7] Though certainly not aware of these more modern interpretations of nostalgia, Americans of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were searching for a means to foster social unity, to find common ties and a connectedness that was lost in the rapid transformations of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Though the research was only recently published, Americans instinctually turned to nostalgia as means to achieve this goal, completely unaware of the psychological functions generated by a nostalgic memory. With the establishment of federal holidays and traditions, de facto national libraries like the Library of Congress and Smithsonian, and parks like Yosemite and the Grand Canyon, Americans grounded themselves in the myths, images, and symbols of their distant past. However, in the amalgamation of common national traditions, some were bastardized and others were combined. Though some facets may have been lost, the final composite represents the American nostalgic tradition of appropriation. As Allison Graham writes, “our apparent obsession with recent history is more an obsession with pseudohistory.”[8]

A NOSTALGIA OF THE FUTURE

Svetlana Boym writes that the 'alluring object of nostalgia is notoriously elusive'. [9] That, however, may no longer be the case. Take the Aitken Bible, printed in Philadelphia in 1781 and 1782, it was the first Bible to be printed in the new nation. In 1782, it received an endorsement from the Continental Congress making it the “Bible of Revolution”. Relics like this are representative of the quintessential pieces of American nostalgia. An original copy of this Bible is now on sale online for $150,000. Nostalgia, in this role, plays an important part of a still nascent nation. With traditions like Halloween and Christmas that we all share, common compendiums of culture like the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress from which was draw our national mythos, and resources made available by projects like Google Books and Snapshots of the Past, nostalgia has never played a more important role.

At the level of the individual, nostalgia represents the desire to gain control over one's life in a time of rapid culture change. It is meant to reflect on one's past acts as means to escape from the bondage of the eternal advancement of time, to create a sanctuary where one can feel safe from the burdensome circumstances of our non-stop culture. It is the through the lens of nostalgia that we as both individuals and as a collective nation work to 'construct, maintain and reconstruct our identities'. [10] Looking backwards to our pasts helps to ground us, gives us a sense of who once were, who we are, and who we will soon be.[11] This work could not be conducted without the tireless work of the nostalgics in the Library of Congress and in the offices of eBay and Google, working tirelessly to catalogue and categorize our national culture on a scale that has never been seen before.

Finally, Americans have begun to slowly create a unified identity that accentuates its own diversity rather than one that hides from it. Originally thought of as a melting pot, where all cultures come to combine into a boiling vat of patriotism, more sociologists are now using the term 'salad bowl', where foods (or immigrants) combine but do not lose their original flavor (or culture) to define American identity. This kind of respect for distinct nostalgic experiences is one that, going forward, should epitomize American culture, identity, and even political movements. Anti-war and civil rights movements of African and Native Americans of the modern era certainly have plenty to learn from those that came in the centuries before them. A denial of this past, and the myths and images surrounding it would deny Americans a true chance to break new ground on the global stage, to emerge as a nation that truly respects not only its original inhabitants, but its incoming immigrants as well.

Perhaps all we need is a truly captivating story.

* * *

This just happens to be a video about nostalgia sponsored by SquareSpace. This website is built using SquareSpace. But SquareSpace did not sponsor this article. Random coincidence.

REFERENCES

PART 1

[1] Fitzgerald, p. 180

[2] Boym, p. xiii

[3] Rousseau, p. 266

[4] Boym, p. 5

[5] Wildschut, p. 975

[6] Boym, p. xiii

[7] Boym, p. 5

[8] Wilson, p. 297

[9] Cross, p. 8

[10] Boym, p. 5

[11] Wilson, p. 299

PART 2

[1] Strauss, p. 263

[2] Chrostowska, p. 57

[3] Chrostowska, p. 63

[4] Graham, p. 351

[5] Chrostowska, p. 57

[6] Barnhill, p. 431

[7] Barnhill, p. 437

[8] Grinde, p. 170

[9] Jung, p. 139

[10] Green, p. 26

[11] Barnes, p. 443

[12] Zagarell, p. 369

[13] Wilson, p. 297

[14] Anderson, p. 255

PART 3

[1] Rogers, p. 50

[2] “Harvest Home | English Festival”, Encyclopedia Britannica

[3] Bruce, p. 111

[4] Bruce, p. 94

[5] "Stamped Cards and Postcards." USPS.com

[6] Chrostowska, p. 54

[7] Grosvenor, p. 87

[8] Hawkins, p. 10

[9] Hawkins, p. 12

[10] Hawkins, p. 27

[11] Hawkins, p. 7

[12] Graham, p. 350

[13] Chrostowska, p. 64

[14] Cross, p. 10

[15] "Fact Sheets." Founding of the Smithsonian Institution.

[16] "Fact Sheets." Facts about the Smithsonian Institution.

[17] Vorman, p. 1

[18] Chrostowska, p. 62

[19] Chrostowska, p. 55

[20] "Our Story." Arcadia Publishing

PART 4

[1] Boym, NPR interview

[2] Boym, p. xiv

[3] "Google Books History." Books.Google.com.

[4] "Google Books History." Books.Google.com.

[5] Nunberg, p. 1

[6] Band, p. 1

[7] Garber, p. 1

[8] Chrostowska, p. 52

[9] Lewis, p. 36

[10] Bjornsson, p. 1

[11] Bjornsson, p. 2

[12] Bjornsson, p. 3

[13] Combs, p. 41

[14] Maney, p. 1

[15] Combs, p. 41

[16] Combs, p. 42

[17] Combs, p. 53

[18] Bybee, p. 154

[19] "Ancestry | About Ancestry." Corporate.Ancestry.com.

[20] Bybee, p. 153

[21] Bybee, p. 153

[22] "Ancestry | About Ancestry." Corporate.Ancestry.com.

[23] Wayner, p. 1

[24] Garrett, p. 1

[25] "Ancestry | Company Facts." Corporate.Ancestry.com.

[26] Bybee, p. 156

[27] "FAQ History of the Company." Snapshots of the Past.

[28] "Notable Customers." Snapshots of the Past.

[29] "FAQ History of the Company." Snapshots of the Past

PART 5

[1] Wildschut, p. 975

[2] Wildschut, p. 976

[3] Sedikides, p. 304

[4] Wildschut, p. 986

[5] Adams, p. 1

[6] Sedikides, p. 307

[7] Tierney, p. 1

[8] Graham, p. 350

[9] Boym, p. xiv

[10] Wilson, p. 301

[11] Wilson, p. 303