Origins of the Historic Bird's Eye View Map

Origins of the Historic Bird's Eye View Map

Source: "The Panoramic Maps of Cities in the United States and Canada", 2 nd ed, John R. Hebert, rev. by Patrick E Dempsey, 1984, Library of Congress.

1. Panoramic Maps

2. Victorian Era

3. Commercial Promotion

4. Cost and Volume of Maps Produced

5. Famous Artists

6. The Most Prolific Panoramic Artist

7. The Bailey Brothers

8. Other Artists

9. Regional Production of Maps

Panoramic Maps

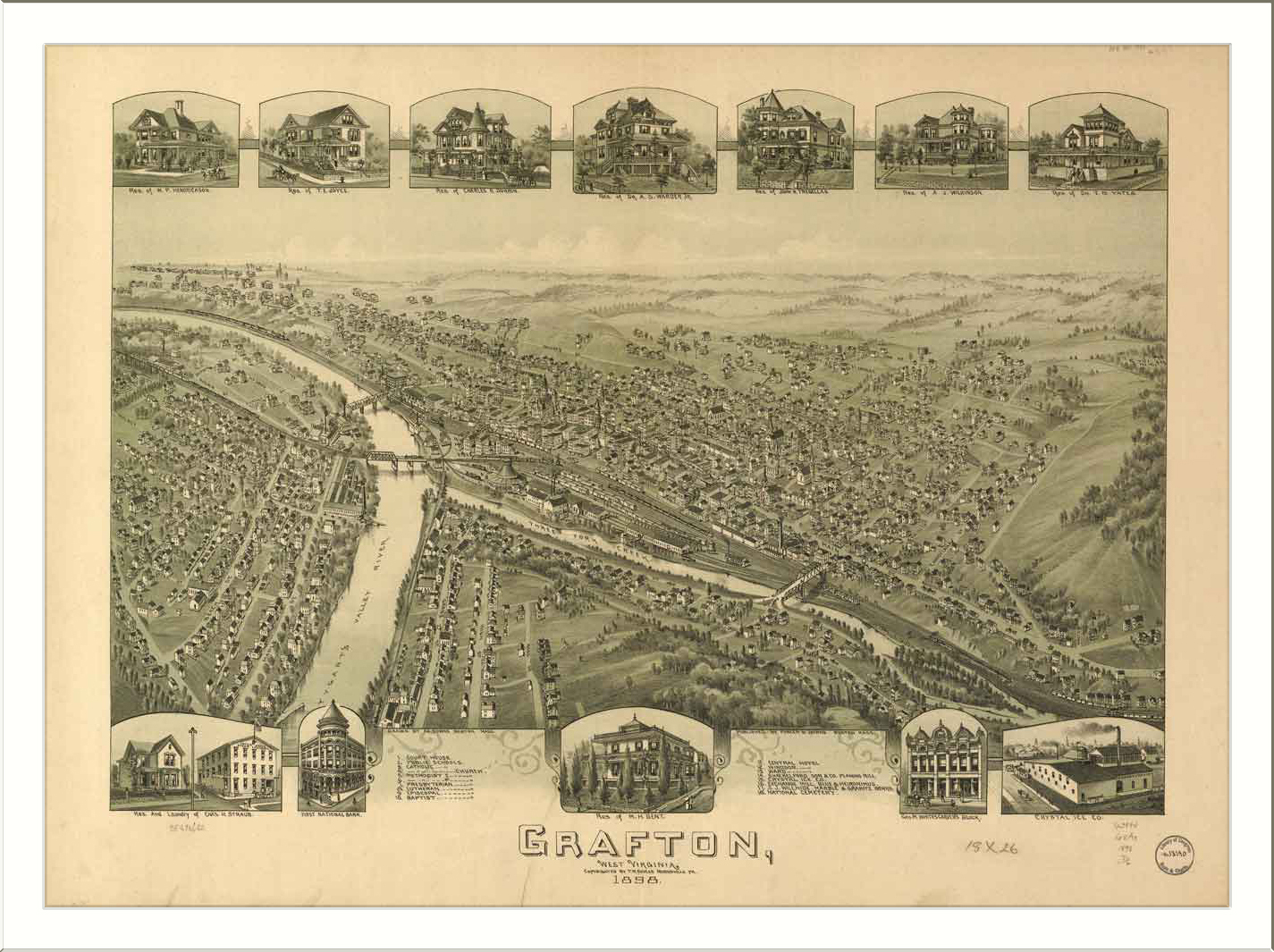

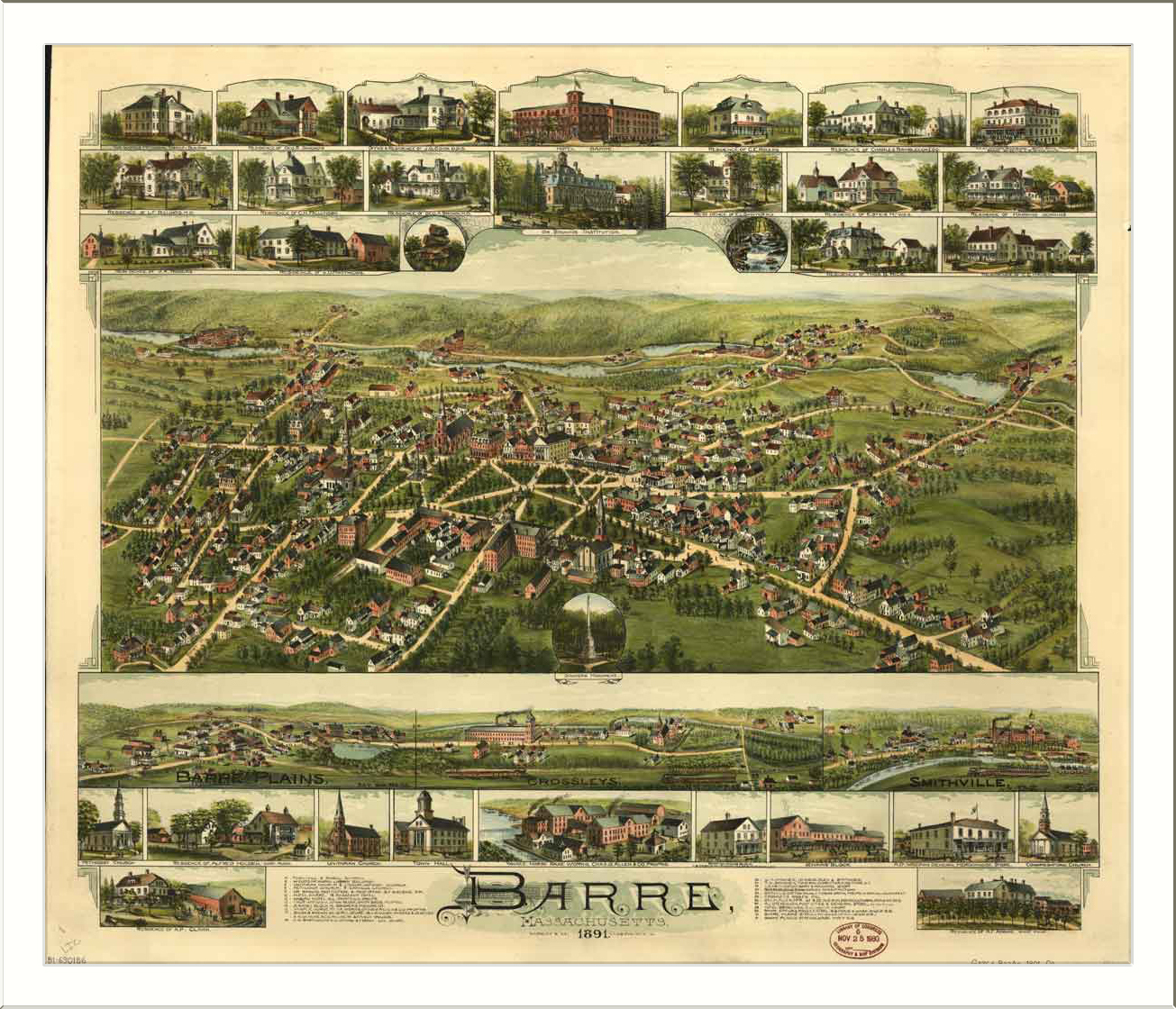

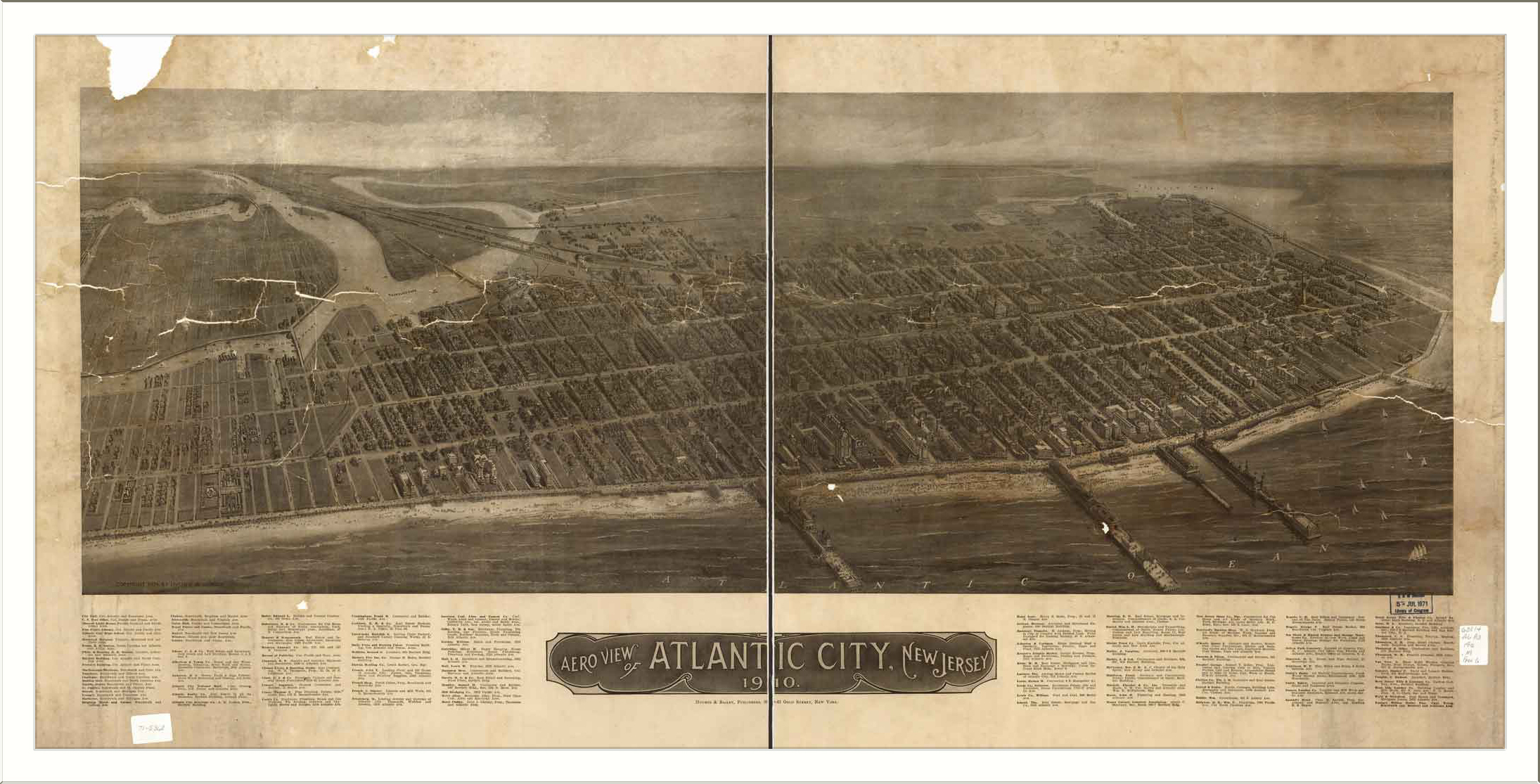

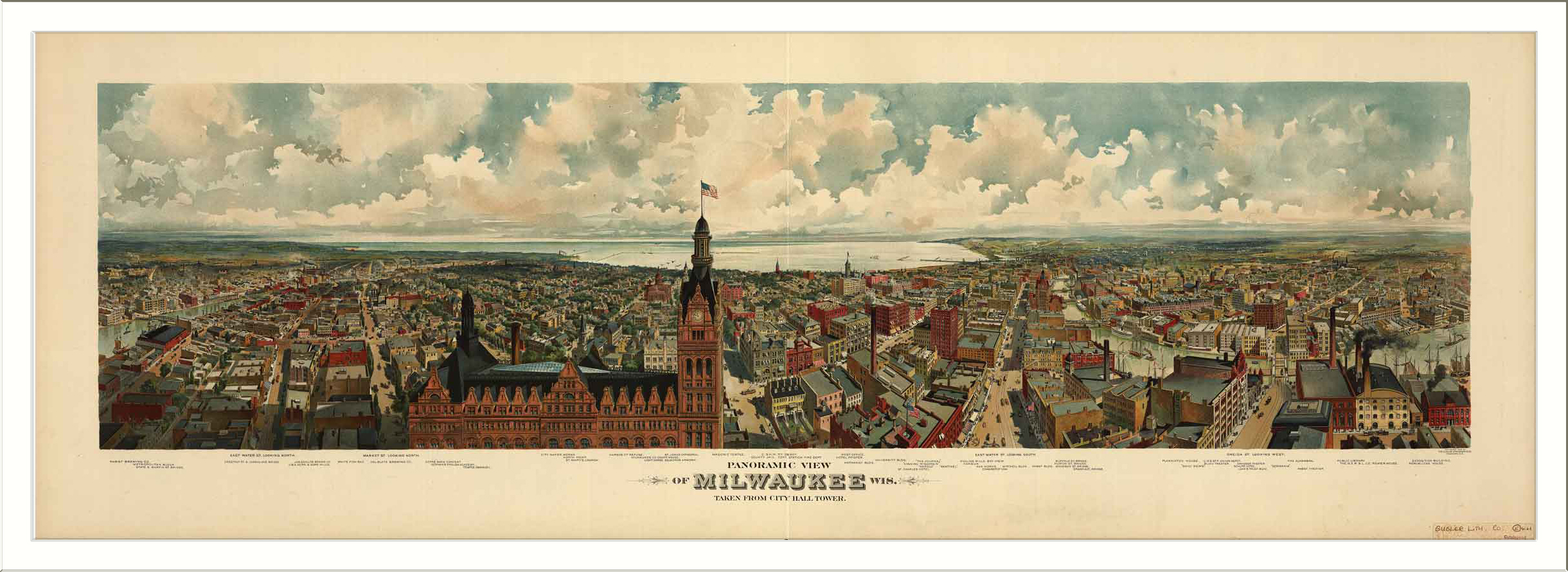

A popular cartographic form used to depict U.S. and Canadian cities and towns during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the panoramic map. Known also as birds-eye views, perspective maps, panoramas, and aero views, panoramic maps are non-photographic representations of cities, portrayed as if viewed from above at an oblique angle. Although not generally drawn to scale, they show street patterns, individual buildings, and major landscape features in perspective.

Preparation of panoramic maps involved a vast amount of painstakingly detailed labor. For each project a frame or projection was developed, showing in perspective the pattern of streets. The artist then walked in the street, sketching buildings, trees, and other features to present a complete and accurate landscape as though seen from an elevation of 2,000 to 3,000 feet.These data were entered on the frame in his workroom.

Perspective mapping was not unique to the United States and Canada or to the Victorian period. Mathias Merian, George Braun, Franz Hogenberg (1), and others produced perspective maps of European cities in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These early European town plans, most often portraying major political or marketing centers, were small in size and were generally incorporated in atlases or geographical books. The perspective was usually at a low oblique angle, and streets were seldom identified by name. In some instances, the views were hypothetical, and one pattern might be used to represent various European cities.

A modified version of the Renaissance city view was employed in the United States before the Civil War. Like their European predecessors, these perspectives, usually of large cities, were drawn at low oblique angles and at times even at ground level. Street patterns were often indistinct. Also popular during this period were views of American cities drawn as though viewed from extremely great heights.

Victorian Era

Victorian America's panoramic maps differ dramatically from the Renaissance city perspectives. The post-Civil War town views are more accurate and are drawn from a higher oblique angle. Small towns as well as major urban centers were portrayed. Panoramic mapping of urban centers was unique to North America in this era. Most panoramic maps were published independently, not as plates in an atlas or in a descriptive geographical book. Preparation and sale of nineteenth-century panoramas were motivated by civic pride and the desire of the city fathers to encourage commercial growth. Many views were prepared for and endorsed by chambers of commerce and other civic organizations and were used as advertisements of a city's commercial and residential potential.

Advances in lithography, photolithography, photoengraving, and chromolithography, which made possible inexpensive and multiple copies, along with prosperous communities willing to purchase prints, made panoramic maps popular wall hangings during America's Victorian Age. The citizen could view with pride his immediate environment and point out his own property to guests, since the map artist, for a suitable fee, obligingly included illustrations of private homes as insets to the main city plan.

Commercial Promotion

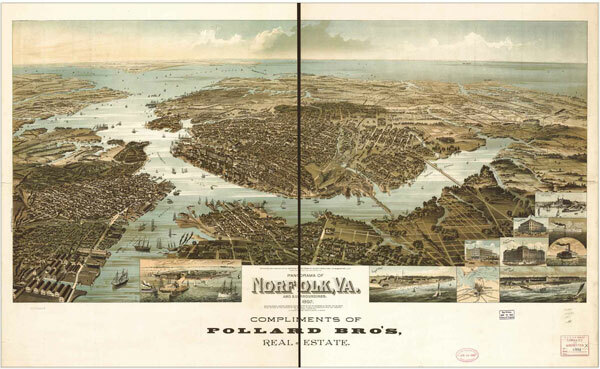

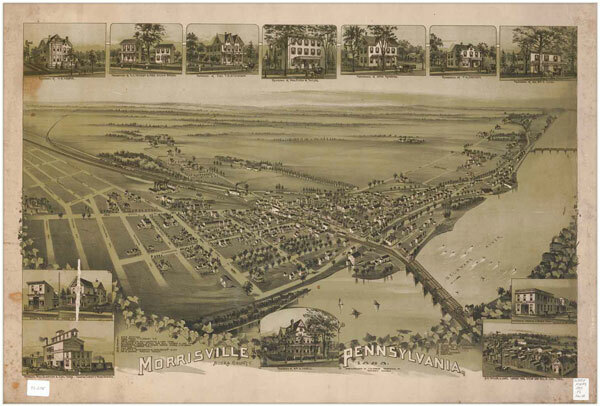

Real estate agents and chambers of commerce used the maps to promote sales to prospective buyers of homes and business properties. Henry Wellge's 1892 panorama of Norfolk, Virginia, for example, was distributed with the compliments of Pollard Brothers Real Estate, and Thaddeus M. Fowler's 1893 view of Morrisville, Pennsylvania, was commissioned by realtor William G. Howell.

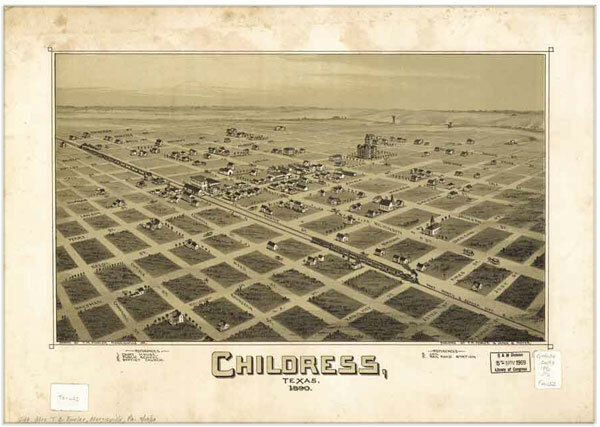

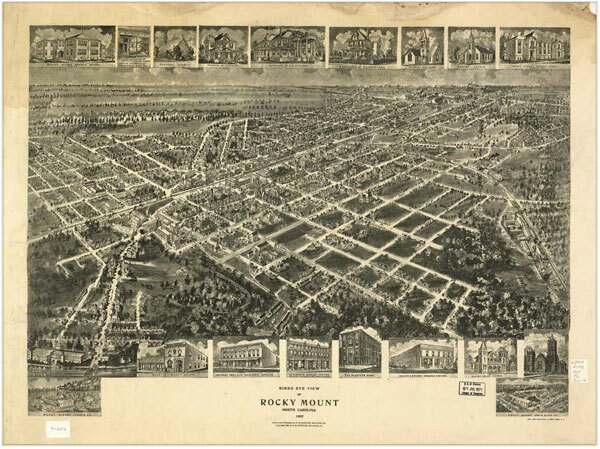

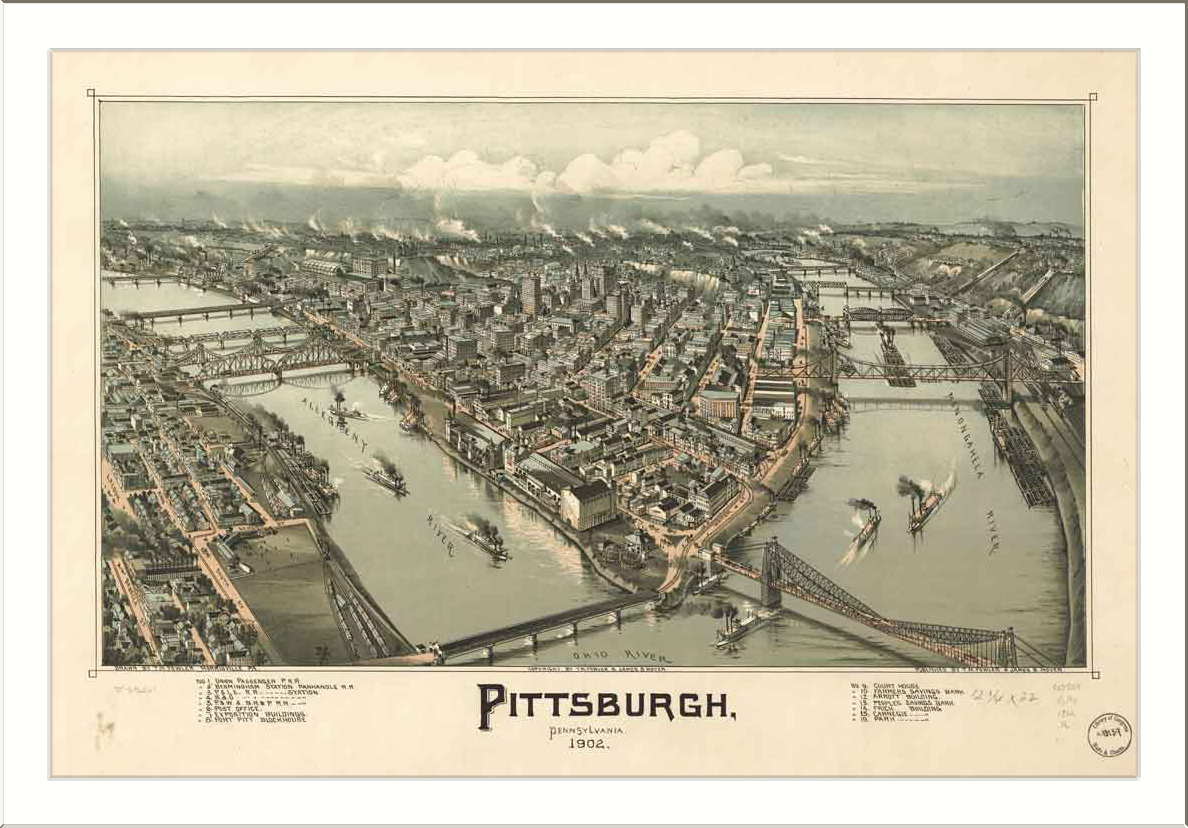

Panoramic maps not only showed the existing city but sometimes also depicted areas planned for development. Fowler's 1890 map of Childress, Texas, and 1907 map of South Rocky Mount, North Carolina, are examples. Panoramic maps graphically depict the vibrant life of a city. Harbors are shown choked with ships, often to the extent of constituting hazards to navigation. Trains speed along railroad tracks, at times on the same roadbed with locomotives and cars headed in the opposite direction. People and horsedrawn carriages fill the streets, and smoke belches from the stacks of industrial plants. Urban and industrial development in post-Civil War America is vividly portrayed in the maps.

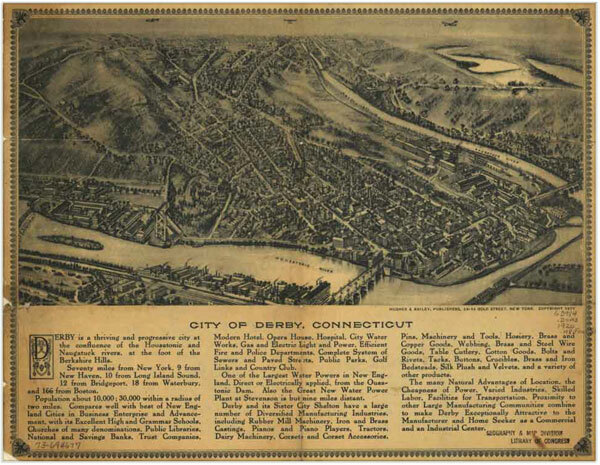

As late as the 1920s, panoramic maps were still in vogue commercially. A view of Derby, Connecticut, by Hughes & Bailey, used on a letterhead of this period, includes a description of the various advantages the city could offer a new industry or a prospective home buyer. The promotional pitch concluded with the following observation:

The many Natural Advantages of Location, the Cheapness of Power, Varied Industries, Skilled Labor, Facilities for Transportation, Proximity to other Large Manufacturing Communities combine to make Derby Exceptionally Attractive to the Manufacturer and Home Seeker as a Commercial and an Industrial Center.

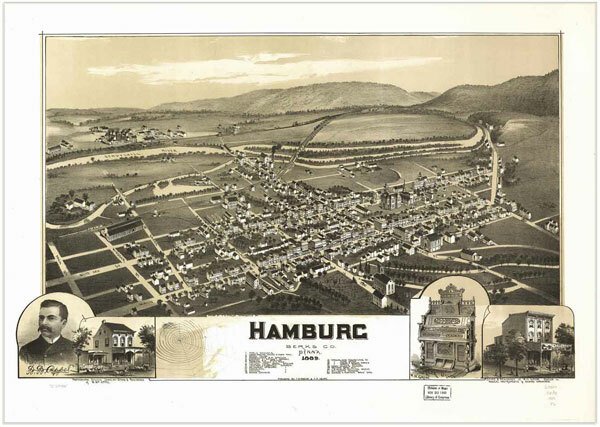

Norris, Wellge & Co.'s 1885 view of Madison, Wisconsin, illustrates another use of panoramic maps. In addition to those sold for wall hangings, copies of the view were used by S. L. Sheldon to advertise his farm implement store. The map is framed by eighteen pictures of farm machines, including the Gasaday sulky plow, the J. I. Case agitator, the Buffalo Pitts coal or wood burning traction engine, and Esterly's twine binding harvester. Sheldon sent copies of the panorama to his patrons, along with a request for their continued patronage. Similarly, Fowler's 1889 map of Hamburg, Pennsylvania, contains two advertisements below the neat line. One portrays W. William Appei's photographic studio, jewelry store, and residence, with a lithographic reproduction of the owner. The other, an advertisement for W. H. Grim, dealer in musical instruments and sewing machines, includes a view of his shop and a representation of a Miller organ, one of Grim's stock items.

Cost and Volume of Maps Produced

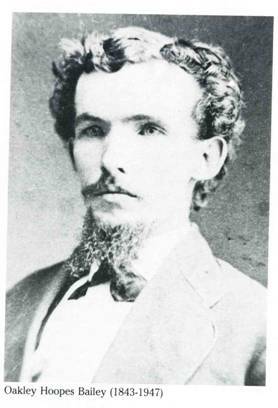

There is little information about the number of prints usually published or the customary selling price. Obviously, more impressions were made of the maps of large cities than of those picturing small towns. An estimate from Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut, the printer of Hughes and Bailey, and Hughes and Cinquin aero views in the 1910s and 1920s, noted that between one hundred and two hundred fifty copies of each view were generally printed. However, Oakley H. Bailey, one of the bird's-eye view artists, stated in 1932 that he had made sketches of nearly six hundred different places and that total reproductions had exceeded a million copies. Simple arithmetic indicates that Bailey's estimate works out to approximately two thousand copies of each view. Considering the scarcity of many views, it may be assumed that the average printing was probably in the neighborhood of five hundred impressions.

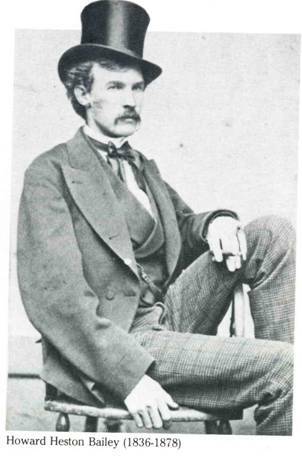

The cost of the individual bird's-eye view was very likely determined by the number of impressions and the buying capability of the citizenry. The following note, appended to H. H. Bailey's 1872 view of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, gives some help:

Our birdseye view of Milwaukee (size 26 x40 inches) is now ready and for sale by all the Booksellers and Stationers... Price $3.00. Our charges for mounting the same on plain frame and varnishing are... 50 cts. For framing in 2½ inch polished Black Walnut Frame, (also mounted and varnished)... $2.50.

Holzapfel and Eskuche, publishers, 443 East Water Street.

This particular view, printed in several colors, was quite handsome. Smaller views and those in two tones did not command as high a price. (Money was not the only exchange medium for views. Thaddeus Fowler reportedly accepted quantities of flour and beans on occasion for his town views) We may assume that the price of panoramic city plans increased during the twentieth century, and therefore, the range in cost was probably from one to five dollars.

The most successful print publisher in the nineteenth century was the firm of Currier & lves. Best remembered for their views of daily life in Victorian America, they also prepared bird's-eye views of New York City, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, and Washington. However, they were not a leading panoramic mapmaking firm, and their distinctive views were primarily of large cities. Most post-Civil War panoramic maps were of parochial interest, highlighting small cities and towns, and were more detailed than the average Currier & lves' city perspective.

Famous Artists

Albert Ruger, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler, Lucien R. Burleigh, Henry Wellge, and Oakley H. Bailey prepared more than 55 percent of the panoramic maps of the panoramic maps housed in the Library of Congress. Albert Ruger was the first to achieve success as a panoramic artist. The collections of the Library's Geography and Map Division contain 213 city maps drawn or published by Ruger or by Ruger & Stoner. The majority came from Ruger's personal collection which the Library purchased in 1941 from John Ramsey of Canton, Ohio. Before this accession, there were only four Ruger city plans in the Geography and Map Devision. Born in Prussia in 1829, Ruger emigrated to the United States and worked initially as a mason. While serving with the Ohio Volunteers during the Civil War, he drew views of Union campsites, among them Camp Chase in Ohio and Stephenson's Depot in Virginia. He continued to draw after the war, and his prints include a famous lithograph of Lincoln's funeral car passing the statehouse in Columbus,Ohio.

By 1866 Ruger had settled in Battle Creek, Michigan, where he began his prolific panoramic mapping career by sketching Michigan cities. Full descriptions of many Ruger views of Michigan cities are contained in John Cumming's A Preliminary Checklist of 19th Century Lithographs of Michigan Cities and Towns. Towns in some twenty-two states and Canada, ranging from New Hampshire to Minnesota and south to Georgia and Alabama, were sketched by Ruger. He continued his activity into the 1890s, moving his business to Chicago, Madison, Wisconsin, and St. Louis as he sought new markets. In the late 1860s Ruger formed a partnership with J. J. Stoner of Madison, Wisconsin, and together they published numerous city panoramas. Ruger was particularly productive during the 1860s; in 1869 alone he produced more than sixty panoramic maps. In addition to city plans he drew views of university campuses, among them Notre Dame, Shurtleff College, and the University of Michigan. Albert Ruger died in Akron, Ohio, on November 12, 1899.

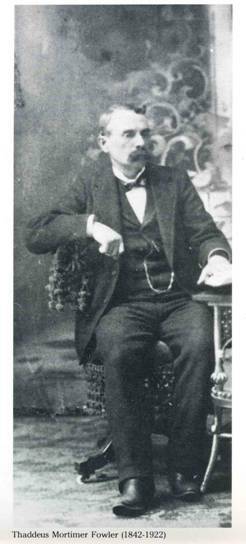

The Most Prolific Panoramic Artist

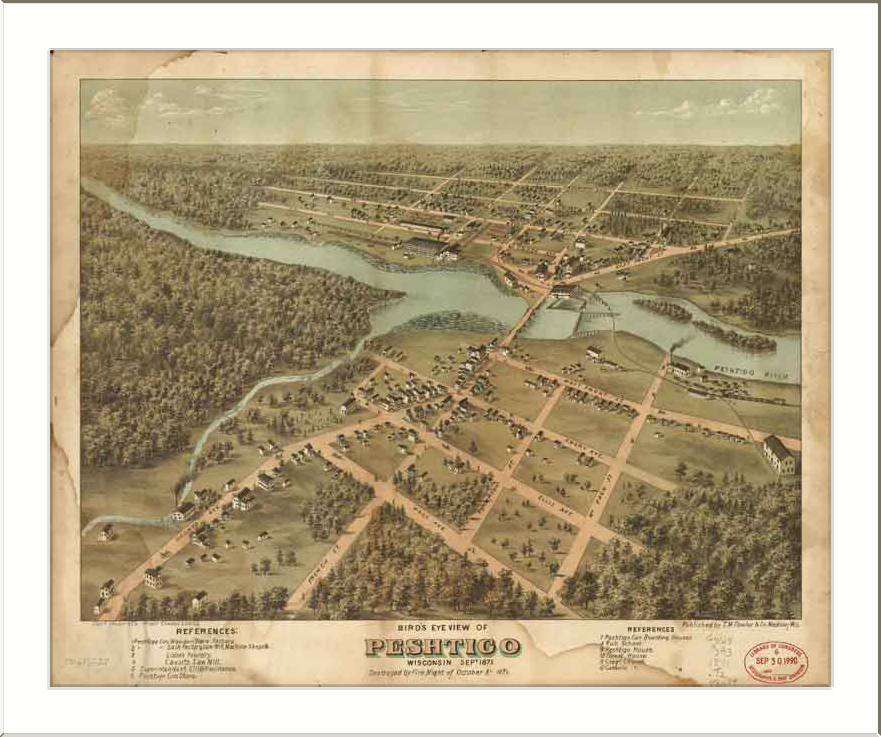

The name which appears on the greatest number of panoramic maps in the collections of the Library of Congress is that of Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler. He was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, on December 21, 1842, and ran away from home at the age of fifteen. When the first call for military volunteers for the Civil War was issued by President Lincoln, Fowler was in Buffalo, New York. Although initially rejected because he was underage, after some maneuvering Fowler was sworn into the 21st Regiment of the New York Volunteers at Elmira, New York, in May 1861. He received an ankle wound at the Second Battle of Bull Run and was honorably discharged at Boston in February 1863, leaving the hospital on crutches after refusing amputation. He then visited army camps where he made tintypes of soldiers. In 1864 Fowler migrated to Madison, Wisconsin, where he worked with his uncle J. M. Fowler, a photographer. He established his own panoramic map firm and in 1870 produced a view of Omro, Wisconsin. This was followed the next year by panoramas of Peshtigo, Sheboygan Falls, and Waupaca, Wisconsin.The Boston Public Library has six views drawn and published by Fowler in the 1870s. During that decade, he was employed as an artist by J. J. Stoner. Fowler moved from Madison around 1880 to northern New Jersey, first to the Oranges and later to Asbury Park.

Between 1881 and 1885, Fowler was located successively in Lewisburg and Shamokin, Pennsylvania, and in Trenton, New Jersey. On April 1,1885, he moved with his family to Morrisville, Pennsylvania, where he maintained his headquarters for twenty-five years. One of the inconveniences of his profession was the recurring need to find new territory for his artistry. In a 1913 request for an increase in his military pension, Fowler noted that "although claiming home where my family was located—I was on the road as Publisher and Canvasser ever since the war."

Morrisville served as a convenient operating center as Fowler began to draw and publish views of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio cities. His production of Pennsylvania panoramas was greater than that of any other artist for a particular state. In the Library of Congress's collections are 220 separate Fowler views of Pennsylvania, representing 199 different towns. There are, moreover, an additional 165 Fowler views of Pennsylvania towns in the Pennsylvania State Archives and at Pennsylvania State University. This is an outstanding record.

At various periods during his career, Fowler was associated with other panoramic artists. The association with James B. Moyer, of Myerstown, Pennsylvania, from 1889 to 1902 was particularly extensive and productive. Some city maps were also published under the imprints Fowler & Kelly, Fowler & Albert E. Downs, and Fowler & Browning. After 1910 Fowler prepared panoramic maps of cities in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York for Oakley H. Bailey, who marketed his prints as aero views.

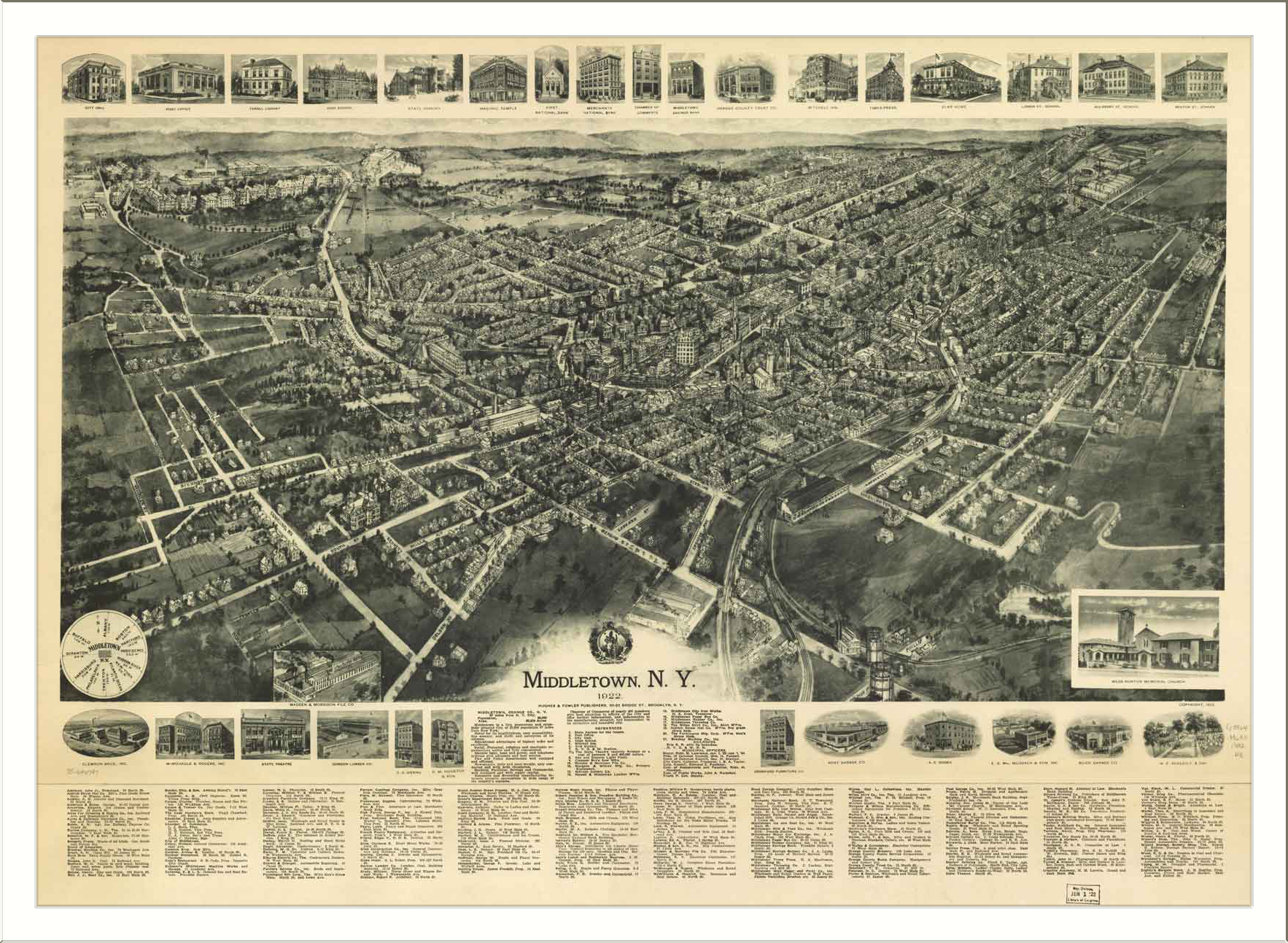

Throughout his career, which extended over fifty-four years, Thaddeus Fowler never ceased to find pleasure in drawing and publishing panoramic maps. In a letter to his granddaughter written in 1920, he said that he felt “an unadulterated joy†while sketching a view of Middletown, New York.

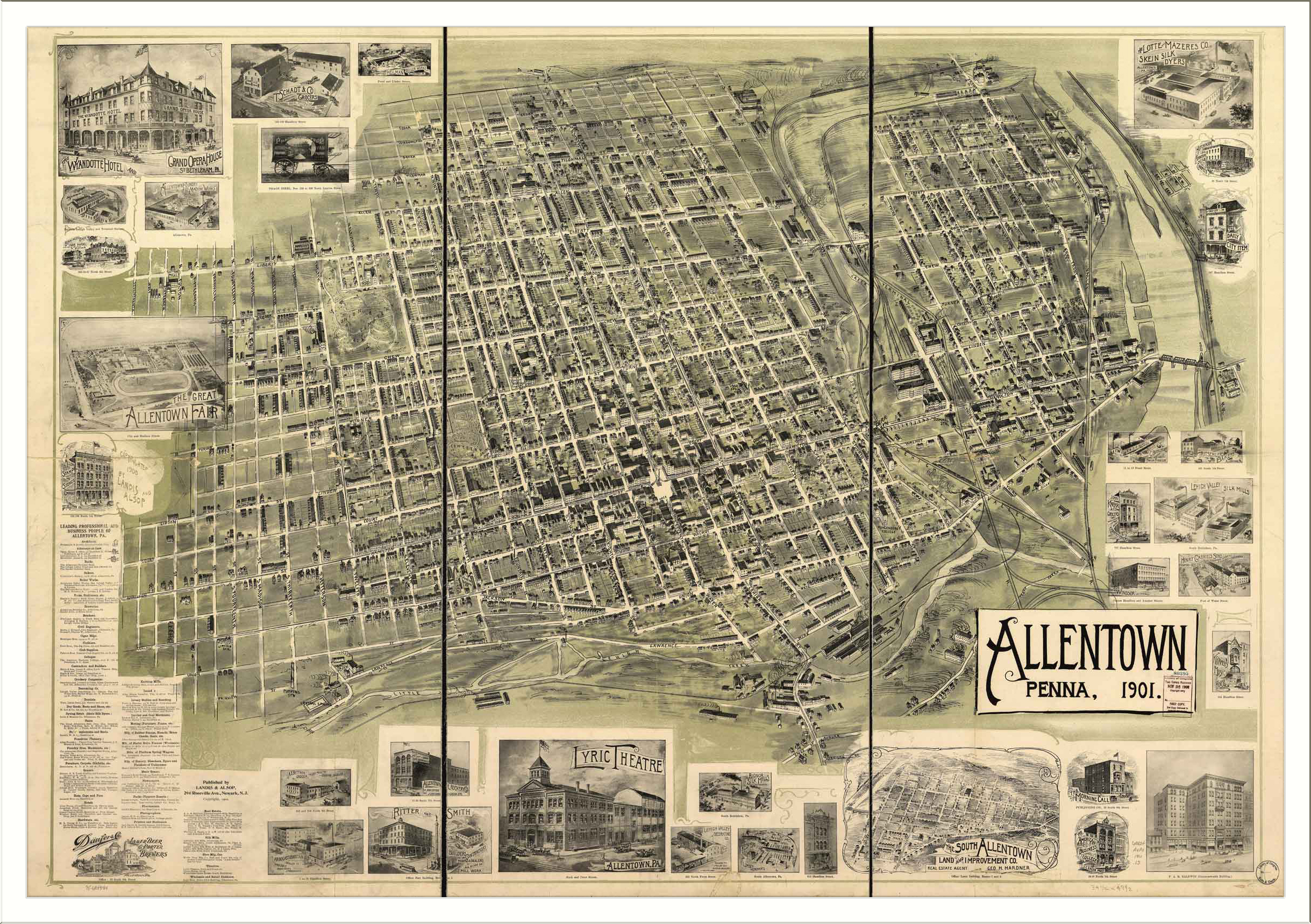

This was the expression of a man who at that time had been working at his profession fifty years! In the same letter Fowler alluded to some of the problems viewmakers encountered. He was in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1918, he recalled, preparing an aero view of the city, probably in association with Oakley H. Bailey. Airplanes and a dirigible circling the city were included in the trademark of the aero view to give the impression that some of the information was derived from aerial reconnaissance, which, of course, was not true. Some Allentown citizens noticed the view with the planes on the manuscript map. In the excitement engendered by World War I, Fowler was accused of being a German spy and was jailed. Members of his immediate family drove from Morrisville to identify their father, who suffered injury only to his pride in the incident. In the 1920 letter previously cited, Fowler also noted that, 'Oakley H. Bailey had taken up my job at Allentown where I left off. The Sec'y of the Chamber of Commerce was very much taken with the drawing as far as I had it done and promised to help. Mayor Gross was very gracious and also favored the idea very much. Quite a different reception Bailey had to mine. There's no doubt we will do well there.'

The Allentown panorama, the largest extant Fowler view, apparently was never published. The magnificent pen-and-ink manuscript with grey wash, which measures 28 by 71 inches, engaged Thaddeus Fowler and Oakley H. Bailey for over four years. A feeling of the city's vitality was expressed by drawings of operating industrial plants, trains in motion, city thoroughfares filled with automobiles and pedestrians, and a group of fans watching a baseball game. The Allentown map was one of the last to which Fowler contributed. He died in March 1922 in his eightieth year, following a fall on icy streets incurred while preparing a panorama of Middletown, New York. Fowler's career spanned the entire period of panoramic map production, and only Oakley H. Bailey shares this distinction.

The views of Thaddeus Fowler include cities and towns in at least twenty-one states and Canada. To date, 411 separate Fowler panoramas have been identified. Of the 324 in the Library of Congress, the majority were acquired on copyright deposit. In 1943, 60 Fowler views of Pennsylvania and West Virginia were purchased from the Laurel Book Service, Hazleton, Pennsylvania, among which are 11 of the Library's 28 Fowler views of West Virginia. In 1970 and 1971 the artist's daughter-in-law Mrs. T B (Roxana) Fowler and her family presented to the Library a collection of over 100 of his maps, 46 of them not previously in the Library's collections. This group has been kept together by the Library as the Fowler Map Collection.

An analysis of Fowler views of Pennsylvania towns suggests that the panoramic artist concentrated on a specific geographical area in a given year, very likely to minimize transportation problems. From 1889 to 1894, for example, he sketched cities in eastern Pennsylvania. In 1889 he focused on Schuylkill County, from 1890 to 1892 he focused on the Scranton and Wilkes--Barre area, and in 1893 he mapped the area north of Philadelphia. He made views of cities between Morrisville and Chambersburg in 1894 and from 1895 to 1897 worked in the western part of the state, especially around Pittsburgh and in the northwest sector of Pennsylvania. In 1898 and 1899 Fowler sketched West Virginia towns and from 1900 to 1903 was back in western Pennsylvania. Subsequently he made trips to Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia to draw city plans and to investigate the possibility of expanding his trade into the South, which proved unsuccessful.

Fowler gained commissions for city plans by interesting citizens and civic groups in the idea of a panoramic map of their community. After one town had agreed to having a map made, he would seek to involve neighboring communities. By noting that he had already secured an agreement for a view from one town in the area, he would play on the pride, community spirit, and sense of competition of adjacent communities. By such promotional procedures he garnered commitments for panoramic maps from a limited geographical area, thus eliminating travel expenses. Similar methods were employed by Ruger, Stoner, and Burleigh.

The Bailey Brothers

There are 127 Bailey items in the Library of Congress, and the Boston Public Library has 242 views drawn or published by Bailey between 1874 and 1891. A Bailey drawing of Atlantic City, measuring over seven feet in length, shows five or six miles of the famous boardwalk, myriad hotels, other buildings, and the ocean front. His maps were issued under the imprints of Oakley H. Bailey, Oakley H. Bailey & Co., O. H. Bailey & J. C. Hazen, Bailey & Fowler, Bailey & Hughes, Bailey & Moyer, Fowler & Bailey, and Hughes & Bailey. In the 1920s the firm of Hughes & Cinquin produced panoramic maps under the sponsorship of Oakley H. Bailey, who had retired in 1927. Perhaps by that time Bailey's eyesight had become too weak to permit him to continue the tedious, close work required of a panoramic artist. He died on August 13, 1947, in Alliance, Ohio, at the age of 104.

Historic Atlantic City. New Jersey, c. 1910 Panoramic Map

When asked in 1932 why he had gone into the panoramic map business instead of farming, Bailey replied that at an early age he had realized that pastoral pursuits were filled with too many uncertainties. He chose instead the career of panoramic map publishing and remained active in it for fifty-five years, drawing and publishing maps of cities in some twenty northern states-and Canada. In a 1932 interview he further noted:

"The business has been practically without competition as so few could give it the patience, care and skill essential to success. But now the airplane cameras are covering the territory and can put more towns on paper in a day than was possible in months by hand work formerly."

Other Artists

Equally as prolific as Bailey in publishing maps of Northeastern U.S. cities was Lucien R. Burleigh of Troy, New York. During the 1880s Burleigh views of New York and New England were particularly popular. An 1883 Troy city directory listed Burleigh as a civil engineer. By 1886 he had become a lithographer and view publisher, publishing under the name Burleigh Lithographing Company. An advertisement in the 1886 city directory stated that the firm did fine work in all branches of engraving and printing, with aeroviews of buildings and villages a specialty.†Burleigh published panoramic maps as late as 1892, but his most productive years were from 1885 to 1890. Views were published under his personal name and under the imprint Burleigh Lithographing Company or Burleigh Lithographing Establishment.

Henry Wellge, like Albert Ruger, was a Midwestern panoramic map artist and publisher. He worked initially for J. J. Stoner but in the 1880s established his own company. His views of towns in twenty-four states were issued under several imprints—Henry Wellge & Co., Norris, Wellge & Co., and the American Publishing Co. Among other noteworthy panoramic map artists were Herman Brosius, Rene Cinquin, Albert E. Downs, Eli S. Glover, Augustus Koch, George E. Norris, and George H. Walker. Walker was also a successful publisher of atlases and maps.

The urban areas in the Midwest and Eastern United States were of primary interest to panoramic map artists. Several of the artists began their careers in the Midwest, particularly in Madison, Wisconsin, and during the 1860s and 1870s a large number of panoramic maps of Midwestern cities and towns appeared. By the late 1870s the Madison group had dispersed. Ruger and Stoner remained in that city, but Bailey and Fowler moved eastward to virgin territory. The latter two and Lucien Burleigh made the Middle Atlantic and New England states the chief production center for bird's-eye views during the 1880s and 1890s. It was in these areas, moreover, that the panoramic map business had its final flurry of activity in the 1920s.

During the 1860s and 1870s the major publishers and lithographers of panoramic maps were concentrated in the Chicago-Milwaukee area because of the proximity to the artists' center of Madison. Beck & Pauli Lithographers (Milwaukee), Joseph I. Stoner (Madison), and Merchants Lithographers and Chicago Lithographers (Chicago) were responsible for a large percentage of the panoramas. Adam Beck and Clemens J. Pauli operated one of the most active lithographic firms in this area, producing views drawn in thirty states and Canada. Beck and Pauli printed views from 1878 to 1889, being most active during the mid-1880s. Clemens J. Pauli tried his own hand at drawing and printing views in 1889.

Another active producer was Charles Shober, whose panoramas appeared under several imprints, including Charles Shober & Co., Shober & Carqueville Lithographing Co., and the Chicago Lithographing Co. Joseph J. Stoner was the Madison publisher most identified with the Milwaukee-Chicago area panoramic map business. Every major view artist except Lucien R. Burleigh had works published at one time or another by Stoner. By the 1880s publishers and lithographers on the east coast of the United States rivaled the Midwestern companies.

Regional Production of Maps

In the Far West and the South panoramic maps never attained the popularity they achieved in the area north of the Mason-Dixon line, between Maine and Minnesota. Attempts to extend the industry to the South and the West were not particularly successful, although panoramic maps of a few cities in Alabama, Arkansas, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Colorado were produced. Views of communities in the state of Washington were drawn by Eli S. Glover and Henry Wellge in a span of one or two years in the 1870s or 1880s. Wellge's views of the state, for example, were all drawn in 1884. The South was economically unable to support views of their cities during Reconstruction, and northern canvassers probably would not have been welcome. More significantly, perhaps, the focal point of life in the South was the farm or plantation, not the village or town as in the Midwest and the Northeastern states.

Similarly, the panoramic map business never gained in popularity in Canada. The Public Archives of Canada has 112 unique panoramic maps of which 48 are original views. The Library's collection includes the largest panoramic map published, Camille N. Dry's 1875 Pictorial St. Louis; The Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley, which was dedicated to the famous Mississippi River bridgebuilder Capt. James B. Eads. It was produced on 110 plates, which when trimmed and assembled created a panorama of the city measuring about 9 by 24 feet. Dry issued the panoramic map in an atlas, the preface of which included the following notes regarding its preparation:

A careful perspective, which required a surface of three hundred square feet, was then erected from a correct survey of the city, extending northward from Arsenal Island to the Water Works, a distance of about ten miles, on the river front; and from the Insane Asylum on the southwest to the Cemeteries on the northwest. Every foot of the vast territory within these limits has been carefully examined and topographically drawn in perspective, and the faithfulness and accuracy with which this work has been done an examination of the pages will attest.

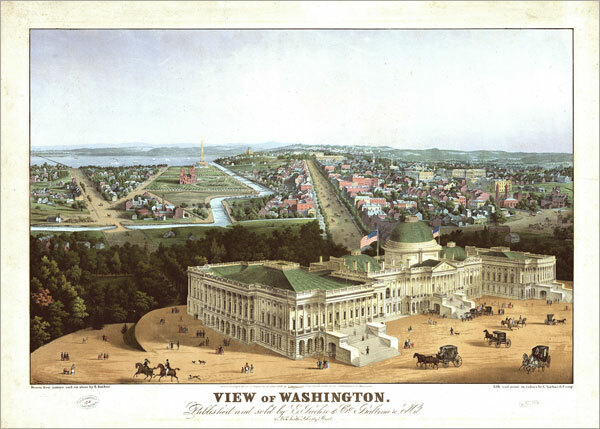

The St. Louis panorama evidently was prepared to show the city’s progress at the United States Centennial celebration of 1876. The verso of each plate contains information on various aspects of St. Louis economic life, including businesses,10 professions, schools, churches, and governmental organizations. Every building in the area was drawn on the map, and 1,999 specific sites were identified by name. A note in the preface requests that any mistakes detected be looked upon with a lenient eye by an indulgent public “in view of the magnitude of the work, the originality of the idea, and the difficulties encountered in carrying it out.†Dry’s map of St. Louis is a magnificent extension of the normal single-sheet lithographic view and one of the crowning achievements of the art. Also impressive for their size and detail are the colored view of Washington (1883-84), which measures 4 by 5½ feet, and that of Baltimore (1869), measuring 5 x 11 feet, both published by the Sachses of Baltimore.

Although the separate print was the most common panoramic map format, views of cities and towns also appeared as illustrations in nineteenth-century state and county atlases. Credit was often not given to the artist in such publications, but some of the leading panoramic map artists probably prepared views for these atlases. Ruger, for example, prepared a landscape view for the title page of E. L. Hayes's 1877 atlas of the upper Ohio River and Valley. The town views in Andrea's 1875 Iowa atlas, although unsigned, also resemble Ruger's work.

Surviving panoramic maps are very popular today and command premium prices from map and print dealers. Facsimile reproductions of panoramic maps are likewise in demand. Panoramic maps give a pictorial record of Anglo-America's cities during the post-Civil War period and, for many localities, provide the sole nineteenth-century perspective of the community. No other graphic form of this era so effectively captured the vitality of America's urban centers.